The Exhibition Reset

How a quiet industry that moves cities, markets, and trust is questioning the very format that made it powerful

Editor’s Note: Who UFI Is — and Why This Matters as the World Shrinks. This extra long form story is anchored in the UFI – The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry Global Exhibition Barometer (36th Edition), a biannual survey of 378 exhibition companies operating across 57 countries, UFI is not an exhibition organizer, a venue owner, or a commercial promoter. It is the global coordinating body for the exhibition industry itself, positioned above individual markets, business models, and national systems. Its role is to observe how industries behave when they feel confident enough to gather physically, invest publicly, and transact in shared space. For that reason, the Barometer functions less as a forecast and more as a confidence index for the physical economy.

This personal analysis is also informed by ongoing dialogue within the U.S. exhibition ecosystem through SISO, which represents for-profit exhibition owners whose businesses rise and fall on exhibitor and attendee performance, and IAEE, whose membership spans for-profit organizers, association-owned exhibitions, venues, and suppliers. Together, these perspectives help translate the Barometer from global data into lived operational reality.

Readers can access the full UFI Global Exhibition Barometer here: https://www.ufi.org/app/uploads/2026/01/UFI_Barometer_36th_Edition.pdfThe Industry

The Industry That Quietly Lost Faith in Its Own Format

For most of its modern history, the exhibition industry has been remarkably good at one thing: getting out of its own way.

Trade shows, fairs, and large-scale business gatherings grew not because they were endlessly reinvented, but because they worked. They worked as marketplaces, as recruiting grounds, as credibility engines, as the places where industries could see themselves reflected back at scale. For decades, the basic architecture of the exhibition — aisles, booths, stages, sponsorships, receptions — proved resilient enough to survive technological change, economic cycles, and cultural shifts that flattened other forms of professional convening.

That quiet confidence is what makes the latest UFI – The Global Association of the Exhibition Industry Global Exhibition Barometer so unsettling.

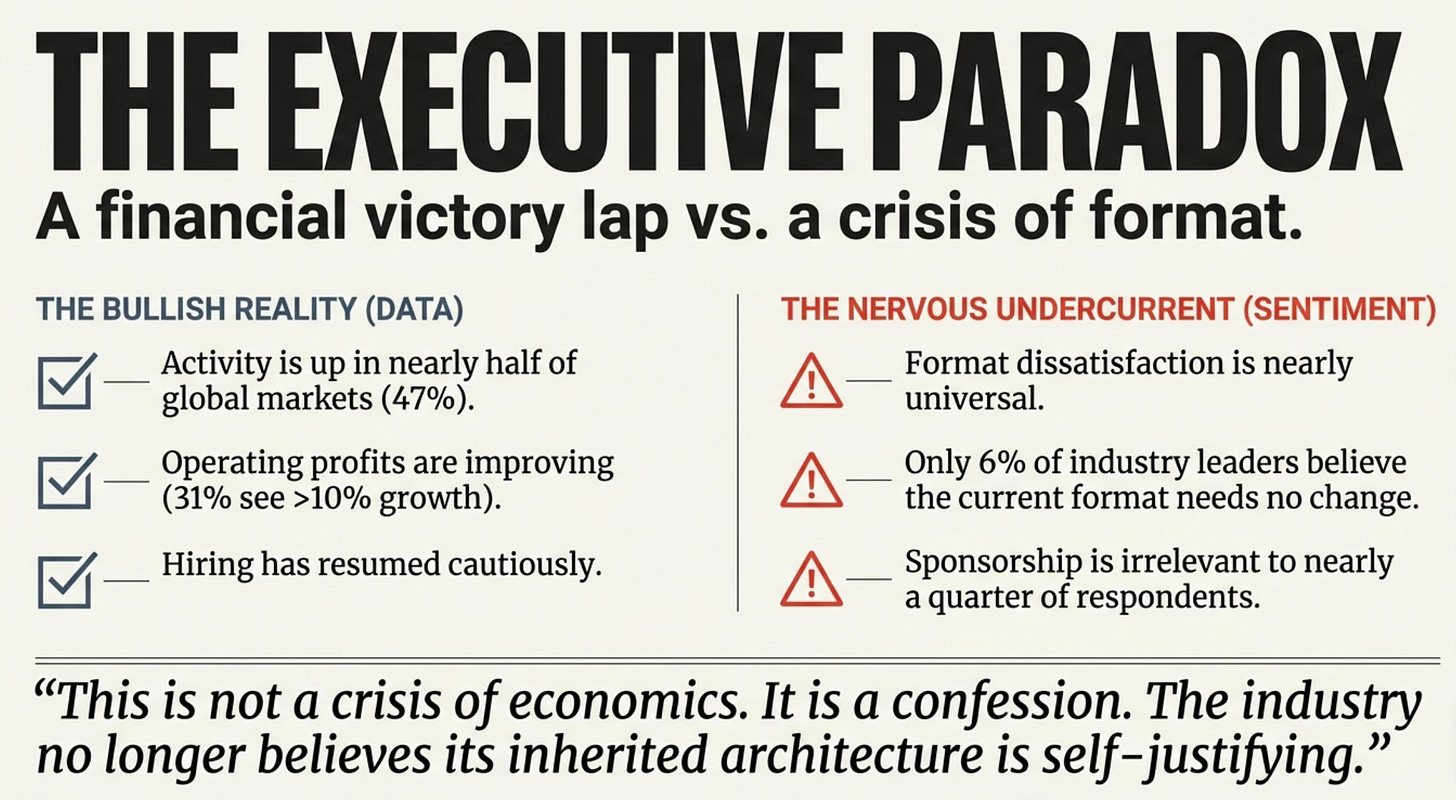

On its surface, the numbers suggest an industry regaining its footing after years of disruption. Activity is up in nearly half of global markets. Operating profits are improving. Hiring has resumed, cautiously but unmistakably. Artificial intelligence, once treated as a speculative add-on, is now embedded across operations to such a degree that it barely qualifies as novelty. In almost any other sector, those indicators would be read as a return to form.

And yet, buried inside the same report is a far more revealing signal — one that has nothing to do with revenue curves or adoption rates

.

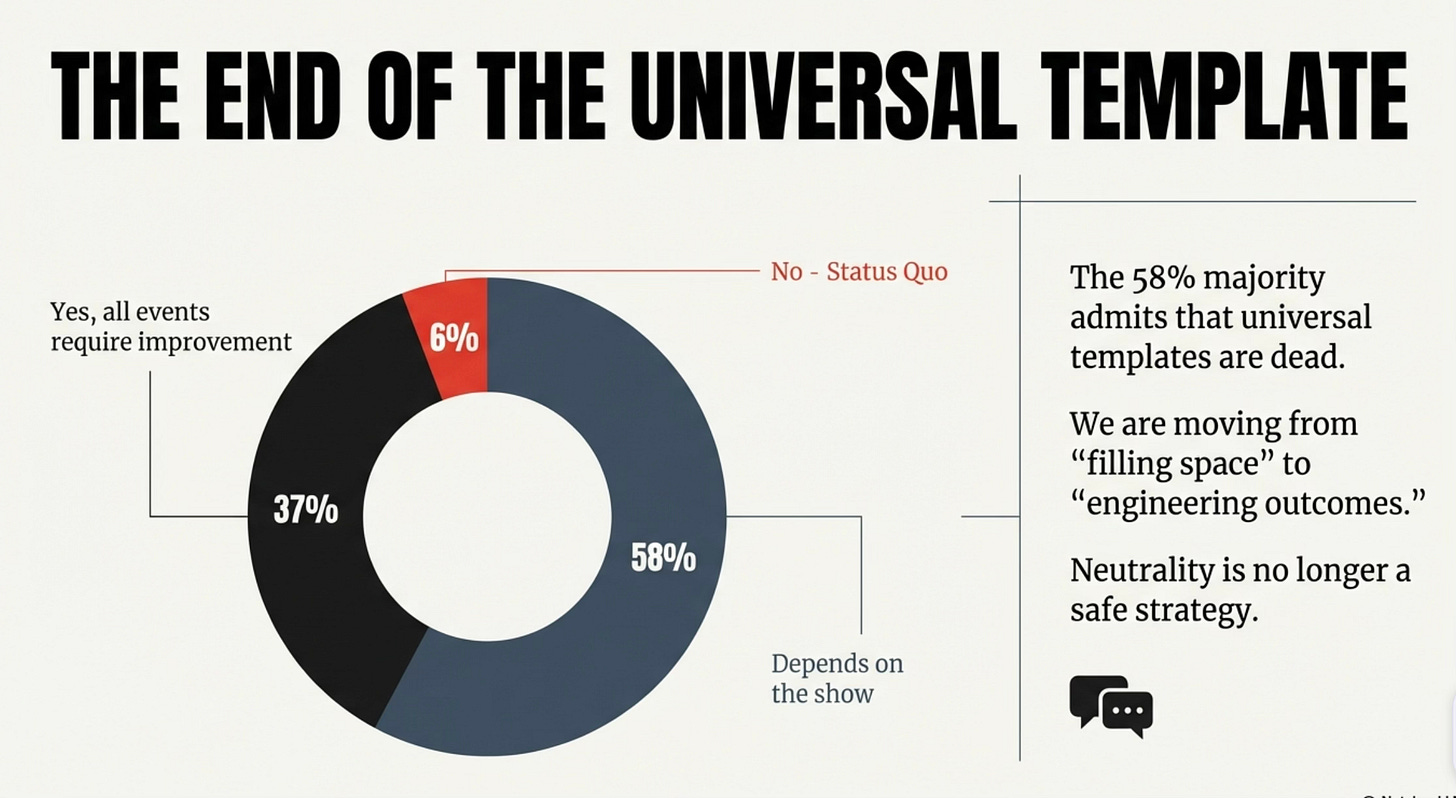

Only six percent of respondents believe the current exhibition format does not need to change. Thirty-seven percent believe all events require improvement. Fifty-eight percent say the answer depends on the show.

In a business built on repetition and scale, that distribution is extraordinary.

It is not the language of collapse. It is the language of doubt — the kind that creeps in not when a system fails outright, but when it continues to function while no longer feeling sufficient. The exhibition industry is not questioning whether it still matters. It is questioning whether the way it has always gathered people still earns the outcomes it promises.

This distinction matters, because industries rarely reinvent themselves when they are losing money. They do it when they sense that success has begun to outpace meaning.

What the Barometer captures, perhaps unintentionally, is the widening gap between economic resilience and experiential adequacy. The business model still works. The format increasingly feels misaligned with the behaviors it is meant to enable. Exhibitors want proof, not presence. Attendees want advancement, not attendance. Sponsors want measurable influence, not impressions. Cities want economic acceleration, not calendar fillers. None of these demands are radical on their own, but together they expose the fragility of assumptions that once went unquestioned.

For years, the exhibition industry responded to pressure by layering on improvements rather than interrogating fundamentals. Better stages. Smarter matchmaking tools. Lounges, activations, keynote names that promised cultural relevance by proximity. These moves were not wrong, but they were additive, not architectural. They assumed the underlying format was sound, even as attention fragmented and expectations shifted.

The Barometer suggests that assumption is no longer widely held.

To understand why, it helps to stop thinking about exhibitions as events and start thinking about them as social systems. At their best, exhibitions compress entire industries into a few days of physical proximity, creating moments where trust is transferred, standards are reinforced, and reputations are recalibrated. That compression is powerful, but it is also unforgiving. When it works, it feels indispensable. When it misfires, the disappointment is amplified by scale.

This is why dissatisfaction with format matters more than dissatisfaction with content. Content can be swapped out. Architecture cannot.

The pressure shows up differently depending on where you sit.

A global organizer overseeing dozens of shows across sectors senses that portfolio logic itself is under strain. What worked for manufacturing does not map cleanly onto technology. What works for healthcare fails in finance. Scale, once the industry’s great advantage, begins to feel like inertia. No single redesign can resolve contradictions baked into a one-size-fits-all approach.

Independent show owners, by contrast, feel the same pressure as a narrowing of options rather than an existential threat. If sponsorship is no longer guaranteed and spectacle no longer sufficient, then differentiation through design becomes not just possible, but necessary. In this reading, the Barometer’s discomfort is an opening, not a warning.

Venues — particularly outside the United States — experience the reckoning even more acutely. In Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, many venues operate under the Messe model, acting not as neutral landlords but as organizers, investors, and stewards of entire industry ecosystems. For them, format dissatisfaction is not abstract. It is balance-sheet risk. When respondents from the venue sector express concern about competition within the industry, they are often speaking as operators whose relevance is tied directly to whether industries still choose to gather in their halls.

Suppliers feel the shift as well, though often indirectly. Demand has returned, hiring is up, and services remain essential, but the quiet realization is that selling inputs into a misaligned system is no longer enough. As organizers and exhibitors push for clearer outcomes, suppliers are pulled toward responsibility for results they once only supported.

Exhibitors and attendees, though absent as direct respondents, are the gravitational force behind every one of these anxieties. Passive participation is losing legitimacy. Big-name speakers, long assumed to be a draw, rank last as value drivers. Learning matters only when it is interactive, recognized, and transferable. Presence must now justify itself against remote access, AI-generated summaries, and a professional culture that no longer equates travel with importance by default.

What makes this moment different from past cycles is not the presence of disruption, but the industry’s willingness to name it. The Barometer does not hedge its discomfort. It does not pretend that incremental tweaks will restore equilibrium. Instead, it reveals an industry standing in a rare in-between space: economically intact, culturally uneasy, and increasingly aware that the logic which once sustained it cannot simply be assumed going forward.

This is not how industries usually announce change. There are no manifestos here, no declarations of reinvention. Just a statistical distribution that, read closely, amounts to an admission that the old model is no longer self-evident.

In mature systems, that admission is often the beginning of real transformation.

The exhibition industry is not searching for relevance. It already has it. What it is searching for now is alignment — between scale and meaning, between presence and outcome, between gathering and value. Whether it finds that alignment through redesign or drift will shape not just the future of exhibitions, but the broader economy of how people choose to come together to do business. That is why this moment matters, and why the quiet doubt captured in the Barometer deserves to be taken seriously.

Five Ways Exhibitions Are Quietly Reinventing Themselves

Industries rarely announce reinvention when it begins. More often, they circle it, naming symptoms before causes, describing discomfort before design. That is exactly what the latest Barometer captures. The exhibition industry is not shouting about transformation. It is describing unease — with format, with expectations, with the widening distance between what gatherings promise and what they reliably deliver.

Out of that unease emerge patterns, not as declarations but as behaviors already taking shape across show floors, session rooms, and sponsorship decks. These are not trends in the way the industry likes to use the word — tidy, forward-looking, aspirational. They are adaptations under pressure, pragmatic responses to audiences who no longer accept presence as proof of value.

The first of these adaptations is the shift from exhibition as display to exhibition as participation. For decades, visibility was enough. Being there signaled relevance; occupying space suggested seriousness. That logic is fraying. Across sectors, exhibitions that continue to privilege static booths and passive observation increasingly feel like catalogs you have to fly to. In their place, a different model is emerging — one that treats the show floor as a site of action rather than exposure. Demonstrations, competitions, hands-on trials, working sessions, live problem-solving. The point is not entertainment. It is trust. When participants do something together, even briefly, credibility transfers faster than it ever did through signage or slogans.

Running alongside this shift is a second, quieter reinvention: the redefinition of learning. For years, conferences and exhibitions treated education as content delivery, a stack of sessions arranged by topic and seniority. The Barometer suggests that audiences are no longer satisfied with that bargain. Learning only matters now when it is interactive, recognized, and usable beyond the room. Credentials, certifications, peer validation, and applied insight are replacing applause as the metric of success. Exhibitions that function as temporary academies, where knowledge is not just consumed but converted into professional capital, are beginning to separate themselves from those that still confuse full rooms with fulfilled audiences.

A third adaptation takes aim at the most overused word in the industry: networking. The Barometer’s emphasis on social engagement does not point to cocktail hours or branded lounges, but to something more intentional. Exhibitions are beginning to treat social interaction as infrastructure rather than filler, designing environments where trust can form deliberately rather than accidentally. Curated dinners, facilitated introductions, off-site experiences, and structured collisions are no longer perks; they are core architecture. In a professional culture increasingly mediated by screens, proximity itself has become a scarce resource, and exhibitions that understand how to design for it are reclaiming relevance.

The fourth reinvention is the most destabilizing, because it rejects the industry’s fondest illusion: that one successful format can serve everyone. When a majority of respondents say that format improvement depends on the show, they are not being evasive. They are acknowledging that sector behavior matters more than scale. A healthcare exhibition does not behave like a technology conference. A manufacturing fair does not produce value the same way a finance gathering does. Universal templates, once the backbone of efficiency, are now a source of misalignment. Exhibitions that are being redesigned around specific industry rituals — how decisions are made, how trust is earned, how progress is recognized — are pulling ahead, while those clinging to generic formulas are discovering that familiarity no longer equals comfort.

The fifth adaptation is largely invisible, which is precisely the point. Artificial intelligence, so loudly discussed on stage, is being deployed most effectively behind the scenes. Matching algorithms, personalization engines, scheduling tools, exhibitor onboarding systems, post-event intelligence platforms. This is not AI as spectacle, but AI as scaffolding, quietly reshaping how exhibitions operate without demanding attention. The Barometer makes clear that most of the industry is still experimenting here, but the direction is unmistakable. As margins tighten and expectations rise, efficiency becomes a design constraint rather than an operational afterthought.

Taken together, these five reinventions do not describe a single future exhibition. They describe a field in motion, responding to pressures that are cultural as much as commercial. Audiences are no longer impressed by presence alone. Sponsors no longer accept impressions without influence. Cities no longer justify halls without impact. Organizers, whether they say it out loud or not, are being asked to prove that gathering still earns its cost.

What makes this moment different from past cycles of reinvention is not the presence of change, but the absence of certainty. The exhibition industry is not converging on a new standard. It is diverging, experimenting, fragmenting into formats that reflect the behaviors of the industries they serve. That divergence can feel destabilizing, especially for organizations built on scale, but it may also be the most honest response to a world in which attention, trust, and legitimacy are no longer distributed evenly.

The Barometer does not prescribe these five paths. It reveals the conditions that make them inevitable. The industry’s task now is not to choose one, but to recognize which combination aligns with the communities it claims to convene. Reinvention, in this context, is less about novelty than about fit.

Exhibitions that understand this are already changing quietly, often without calling attention to what they are doing differently. Those that do not may continue to fill halls, but increasingly struggle to explain why that filling still matters.

The reinvention is not coming. It is already underway.

Why Every Industry Now Needs a Different Kind of Trade Show

For years, the exhibition industry comforted itself with a useful fiction: that while industries differed, the basic mechanics of how they gathered did not. Booths could be resized, programming refreshed, branding updated, but the underlying structure — show floor, sessions, sponsors, receptions — remained stable enough to scale across sectors. Efficiency rewarded sameness, and sameness rewarded scale.

The Barometer punctures that fiction without ceremony.

When a majority of respondents say that whether formats need improvement “depends on the show,” they are not hedging. They are acknowledging that industries behave differently when they gather, and that behavior now matters more than tradition. The result is a quiet but profound realization: exhibitions are no longer interchangeable containers. They are behavioral environments, and those environments must be designed around the way each industry actually makes decisions.

Healthcare was among the first sectors to expose the limits of generic formats. Devices, procedures, and protocols are not evaluated through brochures or slides, but through demonstration and validation. Exhibitions that continue to privilege static display over hands-on proof increasingly feel ornamental. The shows that still command loyalty are those that function like temporary laboratories, where clinicians and buyers can test, question, and observe credibility in real time. In this sector, presence without proof has lost legitimacy.

Manufacturing and industrial markets reveal a different pressure point. Here, decisions are collaborative, capital-intensive, and rarely impulsive. Buyers arrive not to be inspired, but to compare. Exhibitions that succeed are those that allow engineers, procurement teams, and executives to argue product claims against one another in shared space, to test tolerances, assess trade-offs, and simulate outcomes. Aisles that privilege spectacle over comparison feel increasingly misaligned with how decisions are actually made.

Technology exhibitions face perhaps the most existential reckoning. When demos, announcements, and content already live online, the live event must justify itself through what cannot be replicated remotely. Learning must be peer-validated rather than broadcast. Access must be earned rather than sold. Exhibitions that continue to behave like announcement stages struggle to explain why anyone needed to travel, while those that function as concentrated peer communities retain relevance precisely because they offer something digital channels cannot: trusted proximity.

Energy and climate gatherings expose another dimension entirely. These events increasingly behave less like trade shows and more like alignment summits, where policy, capital, and coordination converge. The most consequential conversations are not happening on show floors, but in side rooms, closed sessions, and facilitated coalitions. Exhibitions that understand this dynamic design deliberately for convergence, recognizing that influence in this sector flows through alignment rather than exposure.

Retail, beauty, and lifestyle sectors invert the logic yet again. Here, the product is not merely displayed; it is performed. Trends are adopted socially, credibility is conferred through presence, and influence travels through proximity. Exhibitions that succeed feel less like markets and more like cultural stages, where sensory engagement and social signaling matter as much as transaction. In these sectors, scale is not the enemy, but it must be paired with intimacy, or the signal dissolves into noise.

Finance gatherings, by contrast, punish excess. Information is ubiquitous. Authority is scarce. Exhibitions in this sector succeed when they behave like salons rather than stadiums, prioritizing curation over reach and access over amplification. When scale overwhelms discretion, credibility erodes. The most durable finance conferences are those that understand that reputation, not registration, is the currency being traded.

Hospitality and destination-focused exhibitions reveal another truth the industry has long resisted: when the product is experience, the gathering itself must embody it. Informational formats underperform. Immersion wins. Buyers and partners do not need to be told what a destination offers; they need to feel it. Exhibitions that treat experience as an add-on rather than the core proposition struggle to compete with those that integrate place into every aspect of the event.

Construction and real estate exhibitions sit at the intersection of many of these pressures. Decisions are visual, tactile, and collaborative. Exhibitions that allow teams to walk through scenarios, compare materials, and test assumptions succeed, while those that rely on static display feel increasingly detached from the realities of the built environment. In these sectors, exhibitions function best as decision engines rather than promotional showcases.

Education and association-driven exhibitions are undergoing a quieter transformation, but one no less consequential. Learning alone no longer justifies travel. Advancement does. Credentialing, recognition, and professional progression now determine whether attendance feels like an investment or an indulgence. Exhibitions that connect participation to legitimacy retain relevance; those that do not risk being replaced by alternative credentialing platforms.

Across these sectors, a single truth emerges with increasing clarity. What once felt like best practice now feels like habit. Formats that scale without regard for behavior may continue to fill space, but they struggle to explain why that filling still matters. The future of exhibitions is not about choosing the right format universally, but about aligning design with the way each industry actually gathers, decides, and trusts.

The Barometer does not force this conclusion. It simply removes the illusion that it can be avoided.

No industry gathers the same way anymore. Exhibitions that pretend otherwise will learn the hard way.

How This Analysis Was Built — and Why We Chose to Read the Report This Way

Industry reports are usually treated as objects to be summarized, skimmed for headlines, or quoted selectively to support arguments that were already formed. That approach has its uses, but it tends to flatten the very thing that makes a document like the UFI Global Exhibition Barometer interesting in the first place: its internal tensions. For this package, we made a different editorial choice.

Rather than asking what the Barometer says, we asked what it reveals when read slowly, repeatedly, and from the vantage points of people who carry different kinds of risk. That meant resisting the temptation to extract quick conclusions and instead paying attention to distributions, contradictions, and the emotional temperature of the responses themselves.

The report was read in full, including global aggregates, regional breakouts, and segment-level distinctions among organizers, venues, and suppliers. But the most important work happened after the reading, not during it. We asked the same question again and again: who hears this data as reassurance, who hears it as warning, and who hears it as an invitation to change?

To do that well, we used artificial intelligence not as a shortcut, but as a pressure-testing partner. ChatGPT was employed under strict constraints: no inference presented as fact, no smoothing of contradictions, no summarization masquerading as insight. Its role was to interrogate the data from multiple perspectives — global organizers, independent show owners, venue operators under different governance models, suppliers, financial owners — and to surface where interpretations diverged rather than converged.

Crucially, the process was iterative. We returned to the data repeatedly, refining questions, challenging assumptions, and discarding interpretations that felt tidy but unearned. Where judgment was required, it remained human. Where pattern recognition helped, it was used deliberately and transparently.

This approach reflects a broader editorial belief. The most valuable insight rarely comes from asking a single smart question. It comes from asking the same question many times, from different angles, and refusing to accept answers that resolve too quickly.

The exhibition industry is too complex, too consequential, and too intertwined with real economies to be understood through summaries alone. It deserves to be read the way serious institutions are read: skeptically, patiently, and with an eye toward what is being admitted indirectly rather than declared outright. That is how this package was built, and why it looks the way it does.

Epilogue: What the Barometer Is Really Asking of the Industry

The exhibition industry has not failed, and the UFI Barometer does not suggest that it has. On the contrary, the numbers point to resilience, recovery, and renewed confidence in the basic economics of gathering. Shows are happening. People are traveling. Markets are meeting again in person.

What has changed is not belief in the industry’s relevance, but belief in its inevitability.

For much of its modern history, exhibitions benefited from a powerful assumption: that bringing people together at scale was, by definition, valuable. That assumption held through technological shifts, economic cycles, and cultural change because there were few credible alternatives for physical coordination at scale. Presence itself carried weight. The world no longer works that way.

Information is abundant. Visibility is cheap. Attention is fragmented. Travel is scrutinized. Time away from work must now justify itself explicitly, not symbolically. In that environment, gathering cannot rely on habit alone. It must earn its place.

This is the quiet challenge embedded in the Barometer’s findings. When respondents say formats must change, or that their adequacy depends on the show, they are not rejecting exhibitions. They are asking them to become more intentional, more aligned, and more honest about what they are designed to produce.

That question matters far beyond the industry.

Exhibitions sit at the intersection of commerce, trust, and coordination. They are where industries see themselves reflected back, where standards are normalized, where legitimacy is performed in public. Cities rely on them as economic accelerants. Governments watch them as indicators of confidence. Investors read them as signals of market readiness. Participants depend on them to translate presence into progress.

An institution that carries that much weight cannot afford to drift.

The Barometer does not offer a blueprint for what comes next, and perhaps that is its greatest strength. Instead, it documents a moment when an industry is willing to admit that its inherited forms are no longer self-evident, even as its purpose remains intact. That admission is not a weakness. It is the beginning of accountability.

The future of exhibitions will not be decided by who grows fastest, who builds the biggest halls, or who adds the flashiest technology. It will be decided by who understands, most clearly, why people still need to gather — and who is willing to redesign around that truth rather than defend what once worked.

The reset is not about abandoning scale, tradition, or history. It is about aligning them with a world that no longer gathers out of obligation, but out of necessity.

The exhibition industry is still very much in business. What it is deciding now is what kind of business it wants to be in. And that decision, quietly documented in a set of survey responses, will shape how the world continues to come together — or doesn’t — in the years ahead.