Why Encore Bought FIRST — and What the Deal Reveals About the Future of the Gathering Economy

Why Encore didn’t buy an agency, but an operating system for the future of gatherings

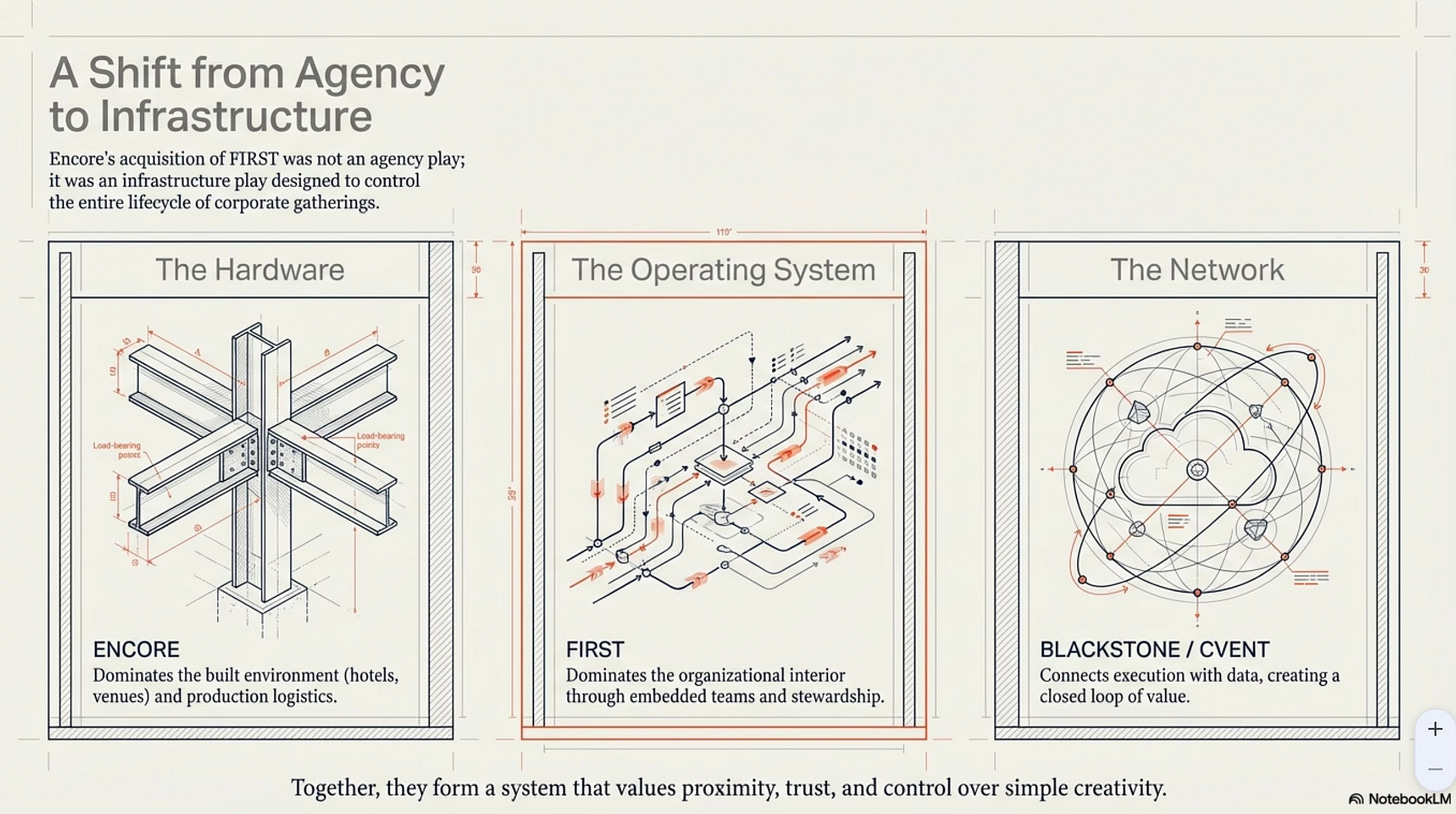

When Encore acquired FIRST, the announcement arrived without drama. There were no claims of disruption, no breathless talk of reinvention, no attempt to dress the transaction up as a creative coup. And yet, taken seriously and placed in context, the deal may prove to be one of the most structurally significant moves the events industry has seen in decades, precisely because it was not about creativity at all. It was about proximity, trust, and control over the systems that now govern how organizations gather.

Encore did not buy FIRST because it wanted another agency. It could have bought many. What Encore already possessed, and possessed at scale, was production muscle and physical infrastructure. Through its legacy as PSAV and its subsequent evolution, Encore embedded itself inside hotels, convention centers, and large venues around the world, becoming less a vendor than a permanent fixture of the built environment. In many places, Encore does not arrive for events; it is already there, part of the building’s operating system.

What Encore did not have was a comparable foothold inside organizations themselves, where the most consequential gathering decisions are made long before a venue is selected or a stage is designed. That is the gap FIRST was built to fill.

For more than fifteen years, FIRST has operated inside major institutions—particularly in financial services, technology, fintech, and consulting—placing dedicated teams within client organizations while retaining full external accountability for staffing, compliance, performance management, and operational discipline. These teams do not appear for a single conference and disappear. They live inside the cadence of the organization, carrying institutional memory across hundreds of gatherings, from executive town halls to investor briefings to global internal summits. Embedded delivery now represents roughly three-quarters of FIRST’s business, a fact that alone explains why this acquisition was never casual.

At the center of that evolution is Maureen Ryan Fable, whose own career arc mirrors the professionalization of the events industry itself. When Ryan Fable joined more than two decades ago to help launch and scale FIRST’s U.S. presence, the firm was still largely project-based, operating as an agency in the traditional sense. The embedded model did not arrive as a master plan. It emerged organically, through repeated client requests that all sounded deceptively simple: Can you stay? Can you take this on? Can you make this your responsibility?

What clients were really asking for was continuity, not staffing. Ryan Fable has long been clear that FIRST never wanted to become a staffing company. The shift occurred when the firm recognized that embedding only worked if it was done with teams, governance, and a defined book of work, rather than isolated roles. That distinction—between filling seats and assuming stewardship—is what allowed FIRST to move inside organizations without becoming invisible or interchangeable.

The roots of that discipline run deeper than the embedded model itself. The story of FIRST does not begin with embedding, or even with the United States. It begins nearly three decades ago in the UK, when Richard Waddingtonfounded the firm originally as First Protocol, building its reputation around rigor, discretion, and an almost ceremonial understanding of how institutions communicate through gatherings. That early focus on protocol was not ornamental. It trained the organization to operate inside environments where trust, compliance, and credibility mattered more than spectacle.

Waddington’s influence did not end when the company evolved beyond its original form. While no longer the day-to-day operating force at FIRST, he has remained a respected and recognizable presence in the global events industry, a figure whose emphasis on discipline and institutional trust shaped an entire generation of practitioners. When Ryan Fable later assumed leadership and re-architected the business for scale, she did so on a foundation already shaped by those values. The evolution of FIRST reads less like a break from its origins than a long arc, stretching from Waddington’s protocol-driven discipline to Ryan Fable’s system-level reinvention.

The earliest proving ground for this model was Wall Street. Long before the industry had language for “embedded teams,” investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley were already outsourcing entire event functions, not because they undervalued gatherings, but because they understood their importance too well. These were institutions where a mis-executed investor event could move markets or trigger regulatory consequences. They had no interest in becoming event companies, yet could not afford improvisation.

Under Ryan Fable’s leadership, FIRST offered a way to externalize the burden without externalizing control. FIRST employees worked exclusively on single accounts, governed by strict compliance firewalls, managed externally by FIRST, and held to standards that often exceeded internal expectations. Contracts were tight. Knowledge sharing across competing accounts was prohibited. Trust was earned slowly and renewed constantly. It was an environment where rigor mattered more than creativity, and where consistency became the ultimate currency.

As procurement leaders moved from finance into technology and consulting, they carried that model with them, often by referral rather than formal RFP. FIRST’s expansion into large corporate campuses extended the embedded approach into environments where event management, guest services, and production needed to function as a seamless, on-premise ecosystem rather than as disconnected vendors. What began as a compliance-driven solution evolved into a professional operating system for organizations that communicate continuously through gatherings.

This is the system Encore effectively bought.

The acquisition becomes even more legible when viewed through the lens of ownership. Encore is backed by Blackstone, which acquired PSAV in 2018 and supported its evolution into a global production platform. Blackstone’s interest was never aesthetic. It was infrastructural. The firm has consistently invested in assets that sit beneath demand—capital-intensive, operationally complex platforms that become indispensable once installed.

Encore does not stand alone in that portfolio. Blackstone also owns Clarion Events, one of the world’s largest exhibition organizers, whose real asset is the repeated convening of entire industries across economic cycles. Through other holdings, Blackstone remains one of the most significant owners of hospitality real estate globally, controlling many of the physical environments where gatherings actually take place. And in 2023, Blackstone acquired Cvent, the dominant software platform through which organizations source venues, manage registrations, track attendance, and evaluate event performance.

Once Cvent is added to the picture, the Encore–FIRST deal stops looking like an adjacency play and starts looking like a consolidation around the most valuable terrain in the gathering economy: corporate-owned events.

Cvent is not an agency or a production company. It is the system of record. It governs which events get funded, which formats are repeated, and which gatherings justify future investment. Placed alongside Encore’s control of physical execution, FIRST’s embedded presence inside organizations, Clarion’s ownership of convening formats, and Blackstone’s hospitality footprint, Cvent completes the stack. Physical layer. Production layer. Organizational layer. Digital decision layer. Not coordinated in some conspiratorial sense, but aligned around a clear capital thesis: the future value of gatherings lies not in spectacle, but in systems that remember.

This context also clarifies why corporate events have quietly become the holy grail of the industry.

Corporate events are owned. Unlike consumer festivals or third-party trade shows, they sit entirely under the control of the organization that produces them. The company owns the audience, the narrative, the cadence, and the data. These events recur annually or quarterly, scale with headcount and global footprint, and justify permanent teams rather than freelance labor. For many organizations, the flagship corporate event has effectively become their own Super Bowl—the moment when leadership shows up, culture is broadcast, strategy is clarified, customers are courted, partners are reassured, and employees are reminded why they belong.

This is why corporate events are growing faster than almost any other segment of the industry. They are resilient across cycles. They generate proprietary data. They reward continuity over novelty. And they favor embedded models that can carry institutional memory forward rather than reset with each new brief.

Seen through this lens, the Encore–FIRST acquisition is not a bet on scale or efficiency. It is a bet on a future in which gatherings are governed the way other mission-critical organizational functions already are: through continuous oversight, evidence-based decision-making, and trusted intermediaries who understand both the machinery and the meaning of what happens when people come together.

Which is why Encore didn’t just buy FIRST.

And why Blackstone didn’t just buy assets.

They are positioning around a simple truth the industry is only beginning to articulate: in the gathering economy, the most valuable events are the ones you own — and the people who know how to run them over time are the real operating system.

Incredible breakdown of how embedded teams work insideorganizations. I never thought about the difference between filling seats versus stewarding the entire gathering system. The way Blackstone positioned around both Cvent and production infrastructure shows a totaly different game being played than most realize. This is the quiet consolidation that actually reshapes how corporate decisions get made.