Washington's Velvet Rope of Influence

How media-hosted events became the most lucrative — and least examined — marketplace for public advocacy

When Semafor raised $30 million in new funding, the signal was unmistakable. As reported by the Wall Street Journal, the company made clear to investors that live events and sponsorships were no longer a side experiment but a central growth strategy, particularly as the digital advertising market softened. The bet was not on traffic or virality. It was on convening — on the durable value of hosting the conversations powerful people want to be seen inside.

That decision places Semafor squarely within a fast-growing but rarely scrutinized economy: the sponsorship market that now surrounds policy media. It is a market defined not by scale, but by precision. Corporations, trade associations, and advocacy groups deploy very large sums of money to position themselves inside a narrow set of conversations that shape regulation, legislation, and reputation. The audiences are small. The stakes are large. The prices reflect that imbalance.

Walk into one of these events and the choreography is immediately familiar. The stage is brightly lit. A senator, regulator, or cabinet official sits opposite a journalist, framed by a sponsor’s logo glowing behind them. The moderator’s questions are polished, calibrated, and tightly timed. Rows of attendees — Hill staffers, lobbyists, corporate affairs executives — sit in the dark, rarely acknowledged and never empowered to steer the discussion. Applause arrives on cue. Cameras capture the angles that matter. The experience feels less like a convening than a broadcast, less like dialogue than performance.

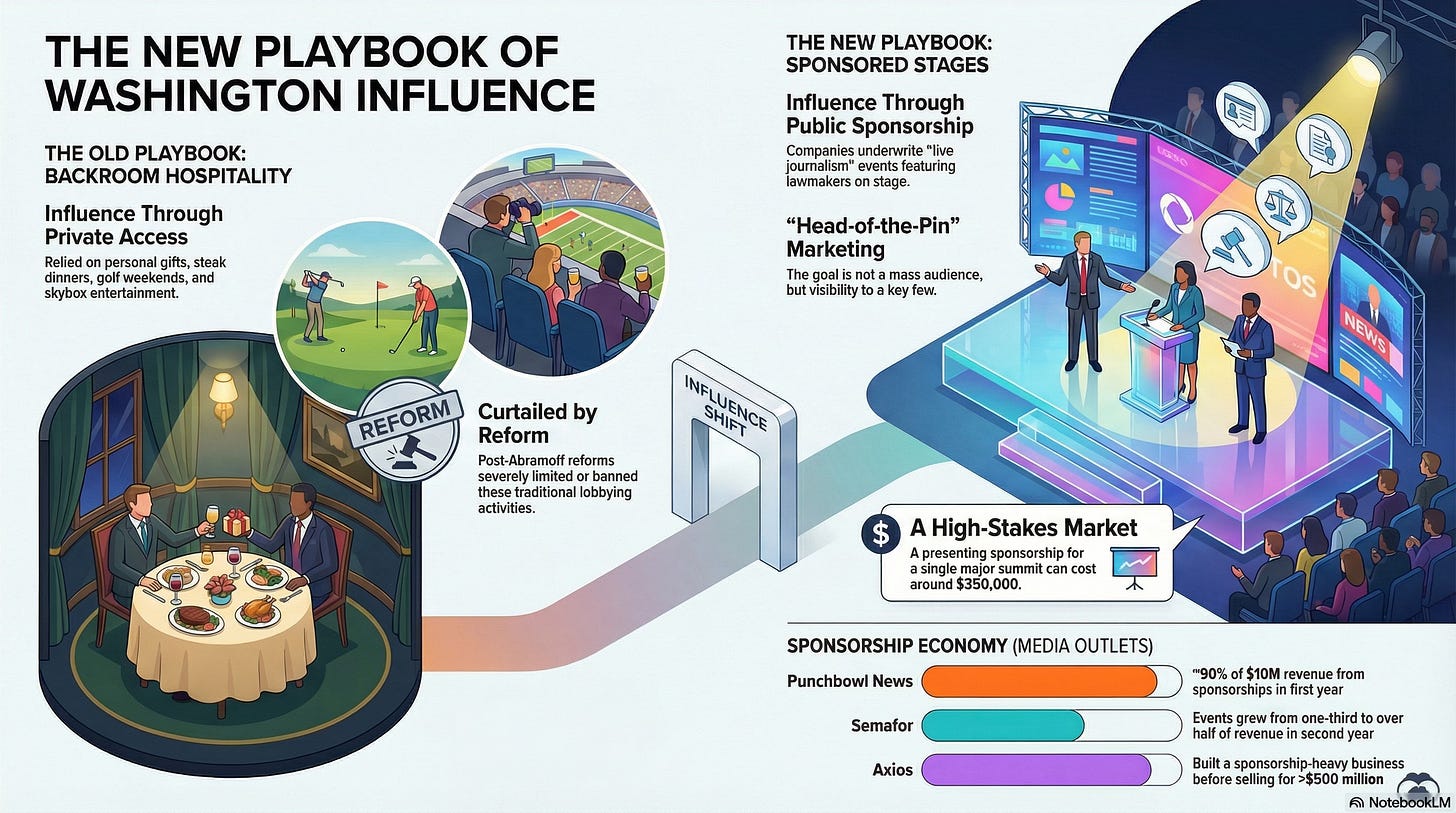

This architecture did not arise by accident. It is the logical outcome of post-Abramoff lobbying reform. After Congress imposed strict limits on gifts, meals, and entertainment, the old rituals of influence — steak dinners, skyboxes, golf weekends, “educational” trips — largely disappeared. Meals were off-limits. Entertainment was forbidden. Alcohol was tightly constrained. What survived was the narrow exception for receptions, where food is incidental rather than the point. Hors d’oeuvres are permitted. Finger food is acceptable. If it can be eaten standing up, preferably with a toothpick, it generally passes muster. That detail became the rule’s nickname. The reforms stripped lobbying of its pleasures but not its instincts. You can’t buy a lawmaker dinner, but you can invite them to speak. You can’t host a private meal, but you can underwrite a forum. You can’t treat them, but you can put them on stage. The fun didn’t disappear; it was rebranded as programming.

Money that once flowed through private hospitality found a compliant, highly visible alternative: sponsorship of events framed as journalism or civic dialogue. A corporation could no longer host a lawmaker over dinner, but it could underwrite the stage on which that lawmaker appeared publicly. The disclosures were legal. The optics were clean. The proximity remained.

Media organizations recognized the opportunity quickly.

Punchbowl News, founded in 2021 by veteran political reporters, generated roughly $10 million in revenue in its first year, with only about $1 million coming from subscriptions. The rest came from sponsorships and events. By 2023, Punchbowl projected roughly $20 million in annual revenue, with sponsorships still forming the bulk of the business. Subscription revenue has since grown rapidly, but sponsorship remains central to the model.

Politico, now owned by Axel Springer, established the model at scale. Its subscription intelligence business provides stability, while newsletters and live events attract major sponsorship dollars from companies and trade groups with active policy agendas.

Axios followed a similar path, building a sponsorship-heavy business before selling to Cox Enterprises for more than half a billion dollars.

Semafor entered this ecosystem with eyes open. From its earliest months, the company treated “live journalism” as a product, not a supplement. In its first full year, events accounted for roughly a third of revenue; by the following year, they represented more than half. Dozens of forums — global economic summits, sector-specific conversations, private dinners — were staged with care, branded with precision, and sold accordingly.

The logic behind this market is straightforward. Public advocacy spending today is not about persuading the public at large; it is about placement. Sponsors are not trying to reach millions of voters. They are trying to remain visible to a narrow group of lawmakers, regulators, senior staff, and the journalists who frame policy debates. In that context, six- and seven-figure sponsorship budgets are not extravagant. They are proportional.

This is head-of-the-pin marketing — a luxury-brand logic applied to governance. Just as Hermès does not need mass adoption, these sponsors do not need large audiences. They need the right room. Scarcity is the product. Prestige is the signal. Presence is the payoff.

What can be established, even without published rate cards, is the order of magnitude of money moving through this market. Based on publicly reported benchmarks, list prices for policy-media newsletters, and the limited number of event sponsorship figures that have surfaced, industry observers place presenting sponsorships for major policy-media events in the low- to mid-six-figure range, with top-tier summits reaching higher depending on timing, topic, and exclusivity. One concrete benchmark exists: Punchbowl News has publicly cited a presenting sponsorship for a major summit at approximately $350,000. Comparable influence convenings — from Davos to Aspen to Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum — operate in the same six-figure band.

What remains deliberately unavailable is a standardized price list tying these figures to specific outlets or events.

That opacity is not accidental. Politico, Axios, Semafor, Puck, and their peers publicly name sponsors and promote sold-out calendars, yet keep sponsorship rates close to the vest. Pricing is negotiated privately, adjusted by timing, topic, and demand. Even prospective sponsors are typically shown opportunity decks that emphasize access and audience composition while reserving actual dollar figures for closed-door conversations. For a market built on visibility, the pricing itself remains largely invisible.

Sponsors justify the spend in familiar ways. They cite metrics: newsletter open rates that routinely exceed forty percent, far above industry averages. They track event attendance, social amplification, post-event reach. They collect qualitative feedback — a staffer mentioning a sponsored forum, a regulator referencing a panel discussion, a journalist adopting a framing that aligns with their interests.

Timing reinforces belief. Sponsorships are aligned with legislative calendars and regulatory moments. When a company underwrites an energy forum during a permitting debate or a healthcare summit during a pricing fight, any favorable movement in the policy environment is often read as confirmation. The term “air cover” appears frequently in these conversations.

Renewals seal the logic. When the same companies return quarter after quarter, year after year, repetition itself becomes proof. If the money keeps flowing, it must be working.

What sponsors rarely claim — and what no one can publicly demonstrate — is attribution.

There is no conversion funnel for influence. No reliable method to trace a sponsored summit to a vote, a rulemaking, or a line of statutory text. Sponsorship ROI lives in a gray zone of inference, anecdote, and fear of absence. As even supporters quietly concede, the logic is often less “we know this changed something” than “we cannot afford to be invisible while everyone else is present.”

The sponsorship itself is often handled with a studied lightness. Logos appear discreetly, disclosures are clean, and the events are framed as journalism first, underwriting second. But when the moment allows — when scrutiny is low or the audience sufficiently specialized — visibility expands. Brand names move from footnotes to backdrops, from program listings to onstage acknowledgments. The calibration is careful. Visibility is dialed up only when it can be defended as contextual, tasteful, or unavoidable. The system knows exactly how far it can go.

Another tell lies in the programming itself. Many of these interviews are deliberately brief — ten or fifteen minutes at most — stacked back-to-back across dense agendas. The goal is not depth but density. Short segments reduce risk, maximize throughput, and allow organizers to cycle as many recognizable names across the stage as possible. Each appearance becomes a credential, each photo a signal that the room mattered, even if no single conversation lingers long enough to challenge assumptions.

This logic is reinforced by the rise of simulcast formats. The primary audience is no longer the people in the room, but the larger, invisible one watching online or encountering the conversation later through clips, newsletters, and social feeds. In that context, intimacy with the physical audience is secondary. What matters is performance. The room exists to generate energy, applause, and visual legitimacy — a set, not a forum.

As Axios co-founder Jim VandeHei has suggested in discussing Axios’s own strategy, influence no longer moves primarily through mass persuasion, including traditional op-eds, but through smaller, more targeted environments where trust, access, and repetition matter more than reach. In that view, gatherings — particularly those that place lawmakers, regulators, executives, and journalists in the same room — are not a supplement to influence but its most reliable delivery system. What happens onstage may be visible, but what happens between the people who attend, speak, and circulate afterward is often where real alignment forms.

Veteran moderators who understand both journalism and convening know how to work a room without surrendering control. Steve Clemons, who has hosted across multiple media platforms and now runs the convening firm Widehall, is often cited as one of them. His work, including high-profile forums at Semafor, tends to favor longer conversations and sustained inquiry. That approach, however, runs counter to the dominant economics of sponsorship-driven, simulcast events, where scale, sponsor visibility, and name density usually take precedence over depth.

Another change runs quietly beneath all of this: the economics of journalism itself. For much of the twentieth century, even the most influential reporters were salaried employees. Prestige mattered; equity did not. That model has shifted. Today’s policy media landscape has produced a small but significant class of founder-journalists and senior editors whose success is measured not only in readership, but in enterprise value — through funding rounds, acquisitions, and ownership stakes. This does not imply compromised reporting, but it does alter incentives. Building durable businesses, scalable formats, and sponsor-friendly platforms becomes part of the professional mandate. Influence is no longer just something journalists cover; it is something their organizations are structured to monetizeLong before any of this was described as “soft power,” Washington already ran on it.

I learned that early, after starting Washington Dossier when I was twenty-one — a magazine focused on social Washington: who gathered where, who hosted, who was seen, who wasn’t. At the time, it was treated as society coverage, not influence. But even then, the dynamics were unmistakable. Access mattered. Presence mattered. The room mattered. What has changed is not the instinct, but the infrastructure. What once moved through dinner tables and salons now moves through stages, sponsorships, and simulcast forums — cleaner, louder, and far more expensive.

The lights dim. The sponsor’s logo fades from the screen. The principal exits through a side door. Attendees file out quietly, returning to offices where decisions will be made elsewhere, later, behind other doors.

The room empties. The ritual resets. And the question lingers, unanswered:

Is this influence — or simply the most expensive table in Washington?

This framing of sponsorship as head-of-the-pin marketing is brilliant. The comparison to post-Abramoff reforms realy clarifies what happened here, the fun didn't disappear, it just got professionalized into "programming." What caught me was the bit about attribution and the lack of conversion funnels for influence. I worked adjacent to this space for awhile and saw the same logic, companies renewing sponsorships year after year not because they can measure impact but because they can't afford invisibility. Feels less like strategic comms and more like paying protection money to remain in the conversation.

Love the observations here. While the focus of this piece is on deliberately media focussed events, there is also a subtle version of this that can infect the influencer bar mitzvah, the celebrity wedding, the blockbuster movie premiere. In those situations the grift is even more deliciously buried!