The Goosebumps Machine and The Future of Feelings at Great Events

What the TikTok Famous Tap Dancing Duo, the Gardiner Brothers — and a Certain Kind of Performance — Reveal About How Large Audiences Actually Connect

I was at PCMA Convening Leaders this past week when something that had been hovering at the edge of my thinking for years finally snapped into focus.

It’s worth saying this plainly. I’m seventy-two years old — slightly older than PCMA itself, which was there celebrating its seventieth anniversary, a milestone that deserves its own separate reckoning and will get it. I’ve been in rooms like this for decades, long enough to know the difference between novelty and something more fundamental.

Which is why what happened next surprised me.

I finally saw the Gardiner Brothers live.

I’ve known them the way millions of people do now, first encountering them as a digital phenomenon on TikTok. Two brothers. Irish step dancing executed with near-mechanical precision. Feet moving faster than seems biologically plausible. Perfect synchronization. Unexpected music choices — Coldplay, Eminem, Ed Sheeran — stitched into a tradition that predates electricity. Videos you replay not because you missed something, but because your nervous system wants to experience it again.

On a phone screen, they are impressive. Delightful. Easy to admire.

In a room, with a live audience, they become something else entirely.

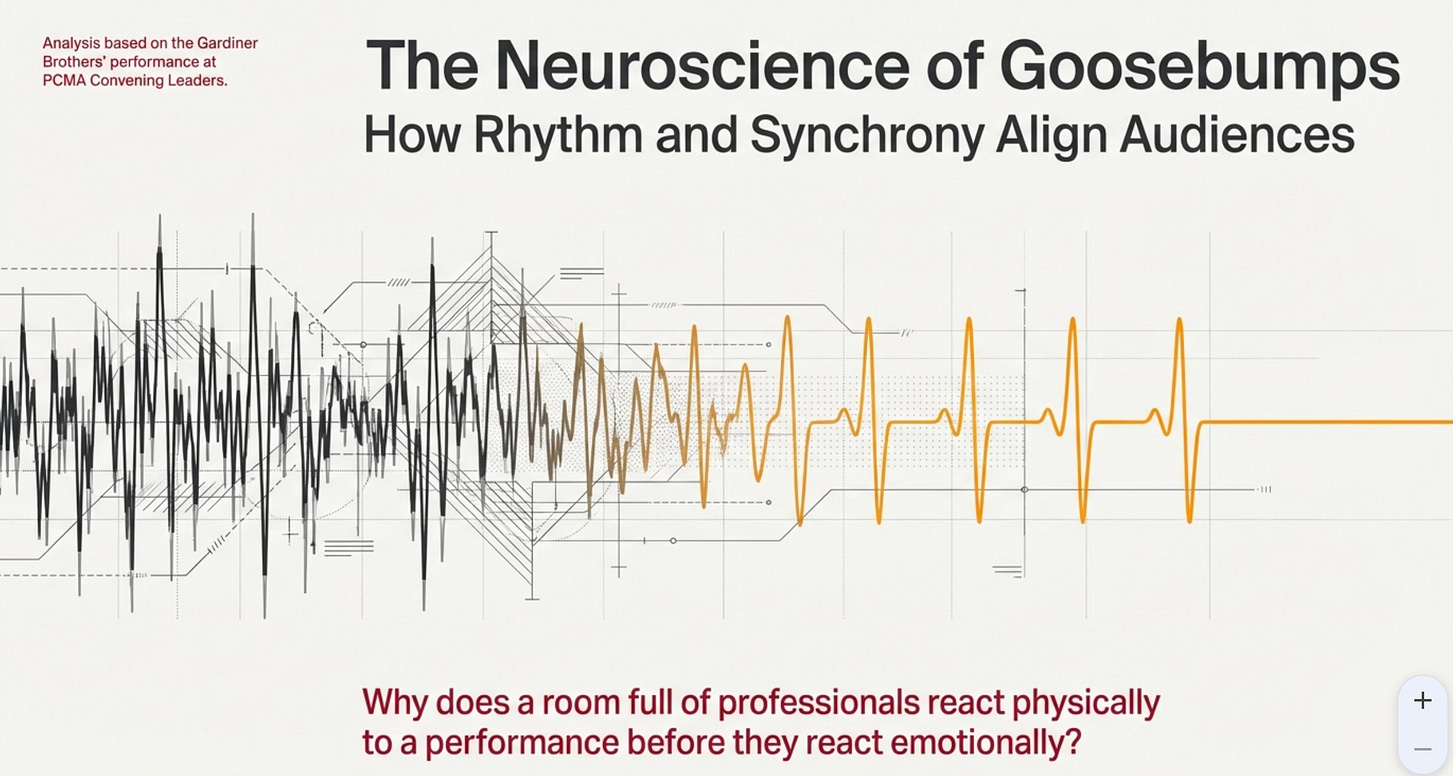

What happened at PCMA was not the usual arc of performance leading politely to applause. It was physical before it was emotional. You could feel the moment land before anyone reacted outwardly. A shared intake of breath. A ripple of laughter without a joke. That visible shiver that moves through people who did not arrive planning to be moved.

Goosebumps. Not figurative ones. The kind your body produces without asking permission.

Standing there, after decades of watching audiences react to keynotes, panels, celebrities, pyrotechnics, and perfectly competent programming, it became clear that I wasn’t watching a performance in the entertainment sense. I was watching brain science operate in real time, at scale.

Goosebumps are not a metaphor. In neuroscience they are known as aesthetic chills — a measurable response involving the autonomic nervous system, the same system responsible for heart rate, breathing, and threat detection. When people experience chills from music or movement, the brain’s reward circuitry releases dopamine at the same moment the body enters a heightened state of attention. Pleasure and alertness arrive together.

That pairing matters.

Most event content stimulates cognition. Goosebumps signal meaning. They tell the brain, without explanation, that something deserves to be remembered.

Brain-imaging research has shown that moments reliably associated with chills activate the same neural pathways involved in motivation, emotional learning, and memory consolidation. In practical terms, this is why people remember concerts from thirty years ago and forget keynote takeaways from last quarter. Emotion is the filing system.

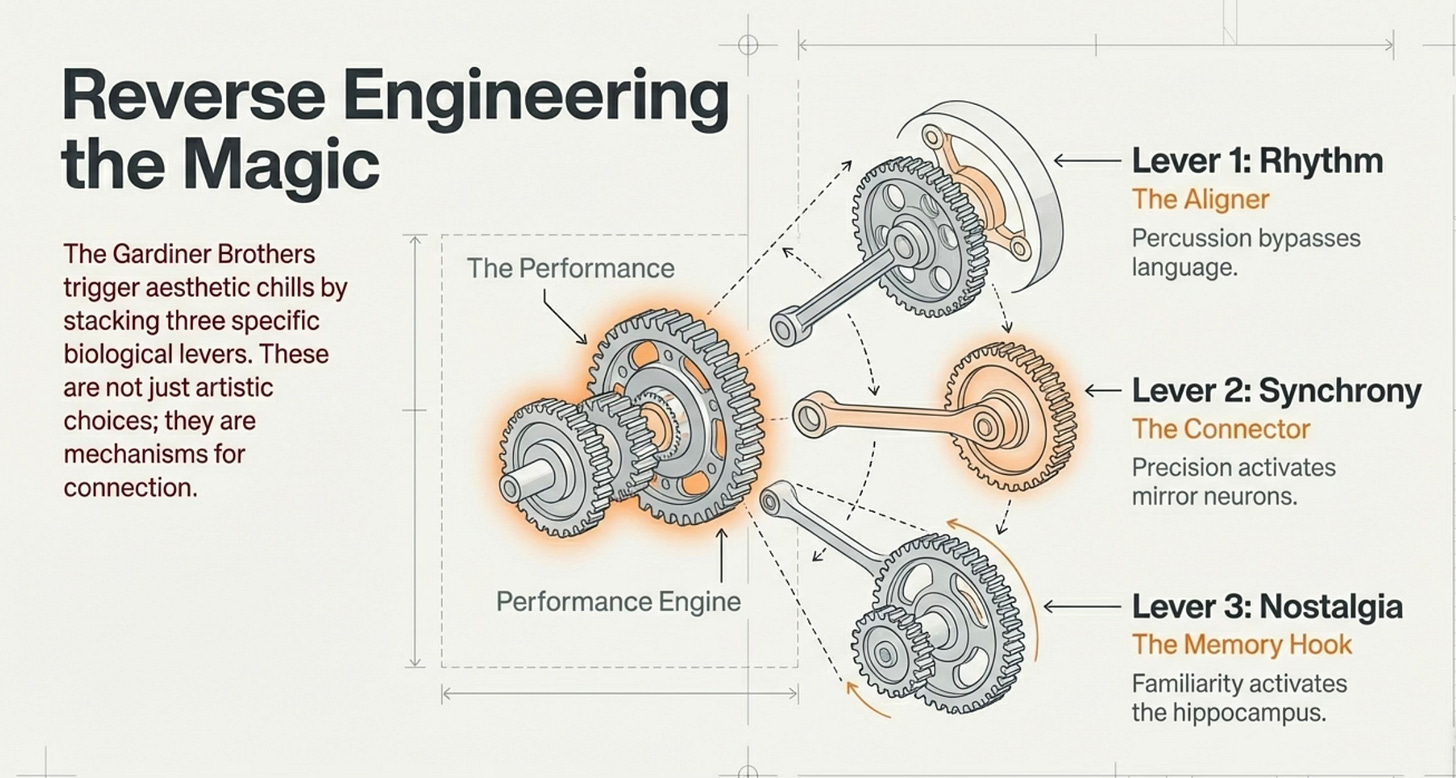

The Gardiner Brothers trigger that response with unsettling efficiency, and they do it by stacking a very specific set of biological levers — the same levers pulled, consciously or not, by a small category of acts that connect large audiences faster than words ever could.

The first lever is rhythm.

Irish step dancing is not ornamental. It is percussive. Their feet strike the floor with force and precision, creating a relentless beat that the body registers before the mind can interpret it. Neuroscience explains why this works so quickly. The human brain has a built-in tendency toward entrainment. When we hear a steady rhythm, neural activity begins to synchronize with it. Motor regions activate even when we remain seated. Feet tap. Shoulders sway. Breathing subtly adjusts.

Rhythm bypasses language. It doesn’t persuade. It aligns.

This is why performances built on percussion and pulse — from drumlines to tap to acts like STOMP — reliably grab rooms full of strangers and turn them into a single attentive organism. During shared rhythmic experiences, people’s neural timing becomes more similar. A crowd begins to behave, biologically, like a group.

Then comes synchrony.

The Gardiner Brothers do not merely dance fast. They dance together, with a precision that borders on unsettling. Synchronization at that level is not just visually impressive. It is neurologically persuasive. When humans observe others moving in perfect unison, mirror systems in the brain activate, creating a subtle overlap between observer and performer. You don’t just watch synchrony. You feel folded into it.

Psychologists have long documented that synchronized movement increases trust, affiliation, and social bonding, even among people who have never met. Part of this effect is chemical. Coordinated movement is associated with the release of endorphins, the same neurochemicals involved in laughter, shared ritual, and physical exertion. This is why armies drill, religions chant, and cultures dance.

It is also why groups like Blue Man Group, precision drum corps, mass choirs, and large-scale movement ensembles consistently produce reactions that feel disproportionate to what is “happening” on stage. Synchrony tells the nervous system that cohesion is present. The body responds by lowering its guard.

And then there is the music.

The Gardiner Brothers do not dance to obscure tracks. They dance to songs people already carry inside them. Neuroscience gives this phenomenon a name as well. Nostalgic music activates the brain’s autobiographical memory network at the same time it activates reward circuitry. Memory and pleasure arrive together. The hippocampus retrieves personal history while dopamine marks the moment as emotionally valuable.

This is why familiar songs crack rooms open.

When the Gardiner Brothers dance to Coldplay or Ed Sheeran, they are not simply modernizing Irish dance. They are triggering thousands of private memory loops simultaneously. Each person recalls something different — a relationship, a road trip, a former self — but the emotional contour is shared. Parallel memory creates collective feeling.

The same mechanism explains why performers like Yo‑Yo Ma, gospel choirs, or even a single pianist playing a universally known melody can quiet a room faster than any MC ever could. Nostalgia is not sentimentality. It is neural efficiency.

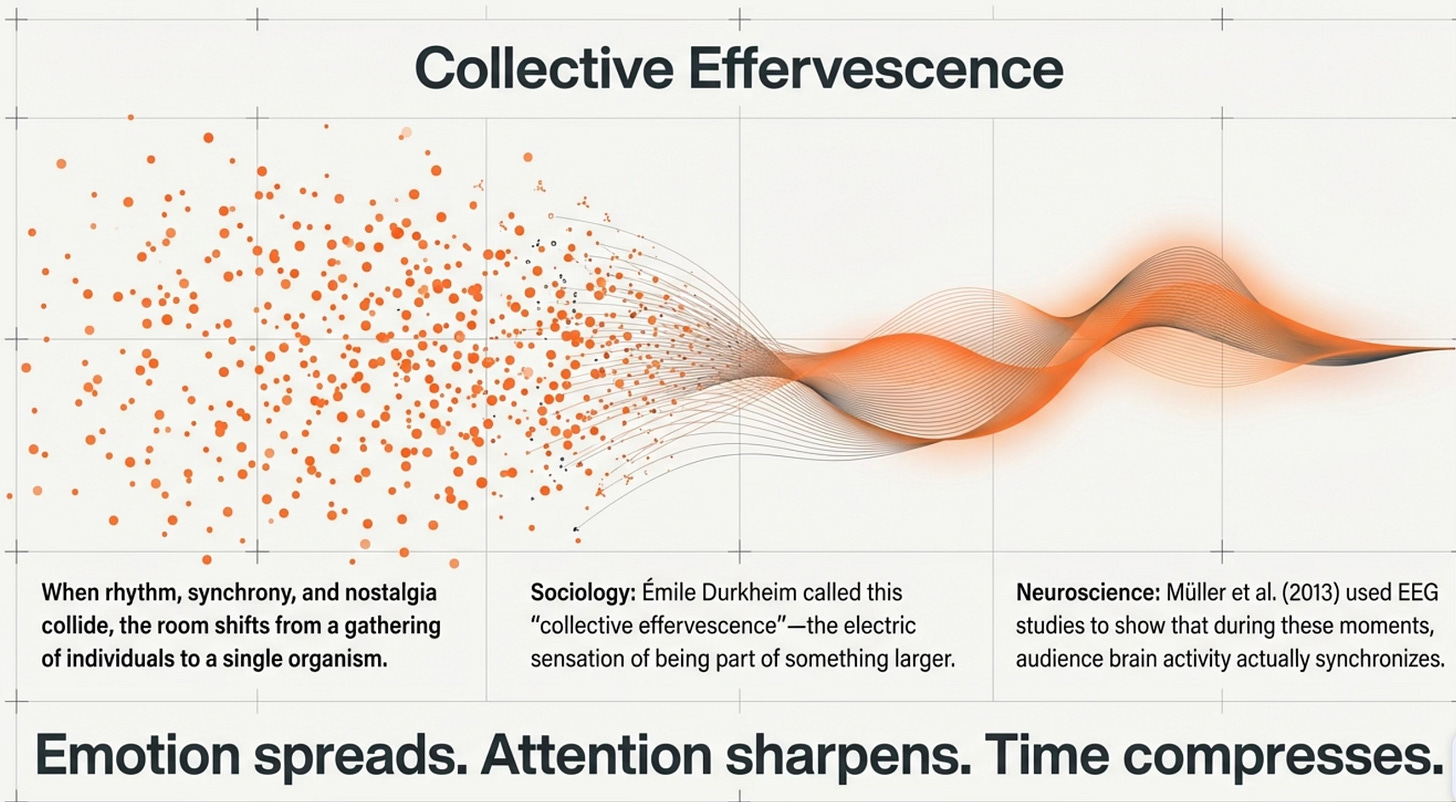

When rhythm, synchrony, and nostalgia collide, something larger emerges. Sociologists have long called it collective effervescence — that electric sensation of being part of something bigger than oneself. Neuroscience now shows that during these moments, people’s brain activity becomes more synchronized. Emotion spreads. Attention sharpens. Time compresses. Applause changes character. It becomes louder, longer, less polite.

Standing there at PCMA, I realized this wasn’t even the first time I’d trusted this effect.

After attending C2 Montréal nearly a decade ago, I quietly rewired how I thought about programming my own BizBash conferences. From that point forward, live music stopped being a flourish and became infrastructure. Walk-on music for speakers. Musicians on stage. Musical punctuation between ideas. Not because I had a Jimmy Fallon complex, but because I could see what it did to rooms. Attention sharpened. Anxiety dropped. Transitions smoothed. People leaned forward instead of checking out. I didn’t have the neuroscience language for it then. I just trusted the pattern. I have also advocated for live music on conference stages even for the most most mundane conferences that normally would never even consider the benefits of this approach.

Teaming up with live musicians even for walk-ons and improvisation was a key for audience engagement as seen here for BizBash Live in Washington D.C.

What the Gardiner Brothers did at PCMA made that instinct legible.

They demonstrated, in minutes, what live music and rhythmic performance have always done when used with intention. They aligned nervous systems before asking minds to engage. They created shared readiness. They made a room receptive before it was reflective.

For event organizers, the implication is not that every conference should book dancers or drummers. It is that there exists a category of performance — across genres, cultures, and formats — that operates directly on the nervous system rather than through explanation. Percussion ensembles. Choirs. Precision movement. Mass participation moments. Artists who work with rhythm, synchrony, and shared memory rather than narrative alone.

These acts do not warm up an audience. They align it.

In an industry obsessed with content, we often forget that connection begins in the body, not the slide deck. Words land only after the nervous system feels safe, attentive, and shared. The fastest path to connective tissue in a large group is not information. It is rhythm that synchronizes, movement that mirrors, and music that reminds people who they have been.

The Gardiner Brothers didn’t just perform at PCMA. They demonstrated, without explanation, something the events industry keeps relearning and forgetting.

Goosebumps are not decoration. They are evidence.

They are the body recognizing belonging — and that may be the most important outcome any gathering can still deliver.

Notes on the Science

Why goosebumps matter

Blood, A. J., & Zatorre, R. J. (2001). Intensely pleasurable responses to music correlate with activity in brain regions implicated in reward and emotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(20), 11818–11823.

Foundational study showing that musical chills activate dopamine-rich reward regions in the brain, including the nucleus accumbens.

Dopamine and peak emotional moments

Salimpoor, V. N., et al. (2011). Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music. Nature Neuroscience, 14(2), 257–262.

Demonstrates that dopamine is released both in anticipation of and during peak emotional moments in music — explaining why build-ups and climaxes are so powerful.

Goosebumps as a physiological response

Grewe, O., et al. (2009). Listening to music as a re-creative process: physiological, psychological, and psychoacoustical correlates of chills. Music Perception, 26(3), 237–254.

Shows that chills involve autonomic nervous system activation (heart rate, skin conductance), not just subjective emotion.

Rhythm and neural entrainment

Large, E. W., & Snyder, J. S. (2009). Pulse and meter as neural resonance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1169, 46–57.

Explains how rhythmic stimuli synchronize neural firing patterns, a phenomenon known as entrainment.

Why rhythm makes us move

Grahn, J. A., & Brett, M. (2007). Rhythm and beat perception in motor areas of the brain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19(5), 893–906.

Shows that listening to rhythmic music activates motor planning regions, even when listeners remain still.

Synchrony and social bonding

Hove, M. J., & Risen, J. L. (2009). It’s all in the timing: interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Social Cognition, 27(6), 949–960.

Demonstrates that synchronized movement increases liking and perceived connection between strangers.

Synchrony, endorphins, and connection

Tarr, B., Launay, J., & Dunbar, R. I. M. (2014). Music and social bonding: self–other merging and neurohormonal mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1096.

Reviews evidence that synchronized movement and music increase endorphin release, strengthening social bonds.

Group rhythm and collective emotion

Dunbar, R. I. M., et al. (2012). Social laughter is correlated with an elevated pain threshold. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 279(1731), 1161–1167.

Uses pain threshold as a proxy for endorphin release, showing that shared rhythmic activity increases bonding chemistry.

Music and autobiographical memory

Janata, P. (2009). The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories. Cerebral Cortex, 19(11), 2579–2594.

Identifies hippocampal and medial prefrontal activation when music triggers personal memories.

Nostalgia activating memory and reward together

Barrett, F. S., et al. (2018). Music-evoked nostalgia: affect, memory, and personality. Emotion, 18(3), 390–401.

Shows that nostalgic music simultaneously increases positive affect and autobiographical recall.

Audience brain synchronization

Müller, V., et al. (2013). Inter-brain synchronization during musical performance. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 344.

EEG studies showing that audience members’ brain activity becomes more synchronized during live musical experiences.

Collective effervescence

Páez, D., et al. (2015). Collective emotional gatherings and well-being. Social Science Information, 54(4), 493–510.

Modern psychological research expanding on Durkheim’s concept of collective effervescence and its role in group cohesion.

Emotion and memory retention

McGaugh, J. L. (2004). The amygdala modulates the consolidation of memories of emotionally arousing experiences. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 1–28.

Establishes that emotional arousal strengthens long-term memory consolidation.

Music, oxytocin, and trust

Keeler, J. R., et al. (2015). Social bonding in music performance: hormonal mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1096.

Evidence suggesting that group musical experiences may elevate oxytocin, contributing to trust and social bonding (an active area of research).

Having sold entertainment for so many years and understanding the relationship between people and music, it continues to be an area of the industry that commands attention and emotion. Hearing a song that is well written and sung is the epitome of evoking feelings that lift our spirits and bring us closer to what matters. Music is relative to who the audience is. Individually it is more powerful than most thing that draw our attention.

“Parallel memory creates collective feeling” resonates deeply with me. Working in higher education, our events are rooted in tradition while also needing to look forward toward progress, possibility, and the what ifs that attract new students and investment. Recently, I opened a major event with a student choir. Mid-performance, I noticed guests with tears on their cheeks, gently swaying in their seats. In that moment, it was clear we were all aligned in a shared belief that investing in students matters.

BTW, I was at that BizBash Live in DC, saw the stage band, and loved the concept. I've since incorporated that idea into many of our events, and the response has been overwhelmingly positive. Would love to see another Live in DC!