The Archaeologist of Place: Vic Isley and the New Power of Destination Leadership

The essential skill set for anyone in destinations: one year after Hurricane Helene, Asheville, NC showed leadership means resilience, culture, and survival—a lesson many places have already learned.

Asheville in the fall of 2024 was the kind of place travel marketers dream of showcasing. The leaves along the Blue Ridge were preparing their annual blaze of gold and crimson, the breweries along the French Broad River were humming, and restaurants by James Beard–nominated chefs were booked out weeks in advance. Travel and hospitality here wasn’t a vanity project; it was the lifeblood.

Nearly three billion dollars in annual visitor spending flowed into Buncombe County supporting a wide variety of businesses in their creative economy—about one-fifth of its GDP—supporting a billion dollars in wages and nearly a quarter of local tax revenue. Explore Asheville the Buncombe County’s tourism development authority, was not only selling the dream. It had already invested close to a hundred million dollars in trails, parks, and cultural infrastructure that made Asheville not just a destination but a lived-in, loved-in place.

And then the hurricane came.

Helene tore into Western North Carolina with the vengeance of history. Mountainsides collapsed into highways. Bridges were washed away. Entire swaths of the Blue Ridge went dark. For days followed by weeks, the Asheville area and other parts of Western North Carolina—a region better known for its wellness spas and craft beer pilgrimages—was without power, without running water, without a functioning communications grid. Breweries couldn’t brew. Restaurants dumped their walk-ins, cooking food by flashlight to feed neighbors and first responders. Hotel managers turned over beds to displaced staff and emergency crews, flushing toilets with pool water. The community that had been thriving on its story was suddenly defined by its survival.

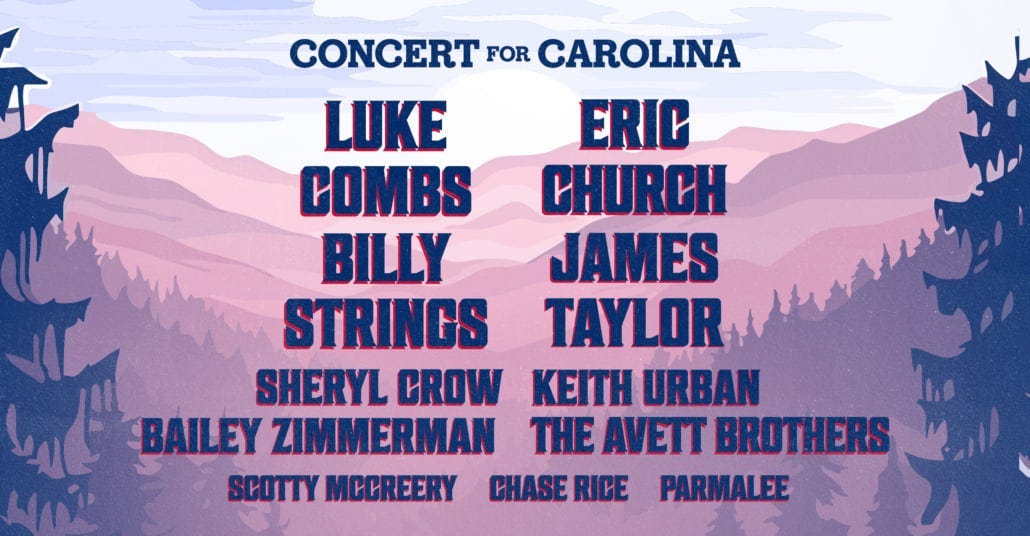

“Information is power,” said Vic Isley, President & CEO of Explore Asheville, recalling those first hours. “The storm hit Friday; by Saturday morning I was on the roof of the new Moxy—its Wi-Fi still worked—calling my sister in Raleigh to relay conditions and start connecting dots.” Her brother, a fire captain in Greensboro, shared that crews were being dispatched to the mountains. Within 24 hours, Isley’s team had shut down all advertising- why waste marketing resources when a city was in crisis?”—and creatively rechanneled marketing dollars into relief. She secured Explore Asheville as the million-dollar presenting sponsor of the Concert for Carolina, a benefit organized by Luke Combs and Eric Church, that brought along James Taylor, Billy Strings, Keith Urban and others to Charlotte’s Bank of America Stadium. The night shattered attendance records and raised more than twenty-four million dollars for Western North Carolina.

This was not marketing. This was leadership.

Vic’s instincts for that kind of pivot were forged far from Asheville’s boutique hotels and breweries. She grew up on a dirt road in the Piedmont, on a tobacco farm, an industry her family has worked in since the 1750s. Vacations were not about jetting to Europe—they depended on whether the crop got harvested. If it did, the family went to Raleigh for the State Fair. “The Ferris wheel was the Eiffel Tower,” she likes to say.

Her father, the first in his family to graduate college, became a civil engineer at NC State. Her mother anchored the family as an elementary school teacher in the rhythm of farm life. Vic headed to Chapel Hill, where she put herself through UNC by waiting tables and working in The Siena Hotel, learning that service wasn’t charm—it was choreography. She sold ads for the Daily Tar Heel and a local visitor guide, discovering how to frame neighborhoods as stories. She didn’t board her first plane until sophomore year—Cancún on spring break—but by then she was already hooked on the idea of place as experience.

It was in her early career years that she met Lynn Minges, then North Carolina’s state tourism director. Selling ads brought Vic into hotel association meetings, and Minges explained what a tourism office was—and what it could do. It was a revelation. The two women stayed close; three decades later they remain friends, as Minges prepares to retire from leading the North Carolina Restaurant & Lodging Association. “The people you meet in this business never really leave your life,” Vic says. That first relationship became the opening act for a career defined by trust and longevity.

Her first official DMO post was in Durham, North Carolina—then the overlooked sibling of the Triangle. In the mid-90s, Durham was seen as the “red-headed stepchild,” yet even then it pulsed with early signals: a food scene from chefs like Ben Barker and Scott Howell that put it on Esquire’s “best new restaurants” list, a creative grit that attracted people who preferred character over polish. Vic says she fell for its “own brand of crazy,” the kind of energy you can’t invent but only discover.

Today, Durham is no longer the underdog. The city has transformed into one of the South’s most vibrant cultural hubs, where the bones of tobacco warehouses have been reborn as arts venues and lofts, where James Beard winners anchor a nationally respected dining scene, where breweries and startups fuel a creative economy, and where Duke University’s global reach intersects with community-driven innovation. The place once dismissed has become a model for how an “authentic brand of crazy” can evolve into a nationally recognized destination.

From Durham she moved to Tampa Bay, where she helped sell the Super Bowl, the NCAA Final Four, and the NHL All-Star Game.

Then came Washington, DC, where she arrived just after September 11, 2001. Suddenly she was running recovery campaigns for a city under siege: airports closed, hotels empty, anthrax in the headlines, a sniper terrorizing the suburbs. She reframed the capital for visitors, positioned the WWII Memorial dedication as national healing, and helped stage Barack Obama’s first inauguration. And she could pivot during the Obamas’ “date night” era, she launched Date Nights DC, crowning Dr. Ruth as “Secretary of Love and Romance” with a box of chocolates, and reframing Washington as a city of intimacy.

Her next role was at Destinations International, where she served as COO of the world’s largest DMO association and Executive Director of its foundation. There she codified professional standards, championed organizational accountability and set the table for “Destination Next”, that would become the futures study for the next chapter in destination management.

From there she went to Bermuda as Chief Sales & Marketing Officer for the Bermuda Tourism Authority, shaping the island’s story around the America’s Cup and broader global campaigns including partnerships with SailGP, the PGA Tour, and the US Open.

And finally, in late 2020, she came home to North Carolina as President & CEO of Explore Asheville, where all those experiences—from Durham grit to DC crisis management to global stagecraft—would converge.

If Vic is the archaeologist of place—digging for cultural DNA in food, music, and community quirks—her partner, Joe Lathrop, is the architect of structure. As President and Founder of OCG International, Joe advised more than a hundred destinations over three decades, pioneering the concept of organizational health and accountability for DMOs. He specialized in board governance and strategic planning and wrote the governance chapter for Destinations International’s textbook. If Vic excavates what makes a place irresistible, Joe ensures the scaffolding holds. Together they embody narrative and structure, curiosity and accountability.

That dual lens mattered when Helene hit Asheville. Vic was climbing to rooftops for Wi-Fi, texting congressmen and managers, cutting advertising and signing stadium-scale relief concerts. Joe’s discipline—governance, accountability, board alignment—meant she had the framework to act decisively and the credibility to bring partners along.

Tourism in Asheville was never frivolous. It was the circulatory system of the destination. When Helene shut it down, the loss was existential: billions in spending, millions in wages, twenty percent of GDP. Pull the thread and the whole fabric sagged: the restaurant server lost shifts, the art gallery shuttered, the craft brewer stopped brewing. Vic saw her job was not to market but to lead, sequencing survival into recovery, and recovery into reinvention

What followed was a civic softening. Asheville is often called the “blueberry in a strawberry pie,” a liberal hub in a conservative region. But when trees blocked mountain driveways, neighbors didn’t ask who you voted for. They showed up with chainsaws. Bipartisan urgency unlocked more than a billion dollars in federal infrastructure commitments. By the next fall, 114 miles of the Blue Ridge Parkway were open again.

The lesson is bigger than Asheville. If the past year proved anything, it’s that the term Destination Marketing Organization no longer fits. Marketing implies campaigns, slogans, brochures. But when your community is underwater, or without potable water for sixty days, there is nothing to market.

There is only leadership.

That’s why the phrase Destination Leadership Organization matters. It captures what these groups have already become: custodians of civic identity, stewards of resilience, conveners of coalitions that hold economies together. Their metrics can no longer be just visitor counts and hotel nights. They must measure GDP impact, wage stability, cultural vitality. They must build resilience playbooks for climate disruption and political volatility. They must invest not only in storytelling but in infrastructure and community benefit. Other destinations like Kerrville, Texas to Pasadena, California have experienced similar challenges since.

Globally, this shift is undeniable. Whether in Asheville, Auckland, or Abu Dhabi, the most effective leaders are those who embrace stewardship as much as marketing. They are archaeologists of culture—unearthing authenticity—and architects of systems that can survive shocks.

Vic Isley has given the industry its proof. She showed how a tourism office can become a lifeline, how storytelling and infrastructure investment intertwine, and how leadership, not marketing, is the word that finally fits.

Destinations, Vic believes, are art. Not the glossy kind, but the kind that shows brushstrokes, imperfections, and layers of history. They are the fingerprints of those who stay and the magnetic pull for those who arrive. They are not brands. They are social contracts.

And so, a year after the storm, the industry has a new moniker for itself. Destination Leadership Organization. And it has its case study in Asheville’s archaeologist of place.