Taking the Industry’s Temperature

Freeman’s new research reveals a quiet shift in how events are judged—and why the future belongs to those who design the room, not just fill the stage

For years, Freeman has occupied a peculiar position in the events industry—less pundit than instrument panel. When expectations shift before language catches up, when audiences quietly change the rules of engagement, it tends to surface first in Freeman’s research. Not because the company chases trends, but because it listens closely enough to notice when behavior starts whispering.

The research Freeman released this week, timed ahead of PCMA Convening Leaders, arrives without drama and lands with force. The Freeman Trends Report 2026 findings will be presented on stage by Ken Holsinger, Freeman’s Senior Vice President of Industry Research & Insights, at a moment when the industry traditionally takes its first hard look at the year ahead. Convening Leaders has long functioned as an annual mirror. This year, the reflection is sharper.

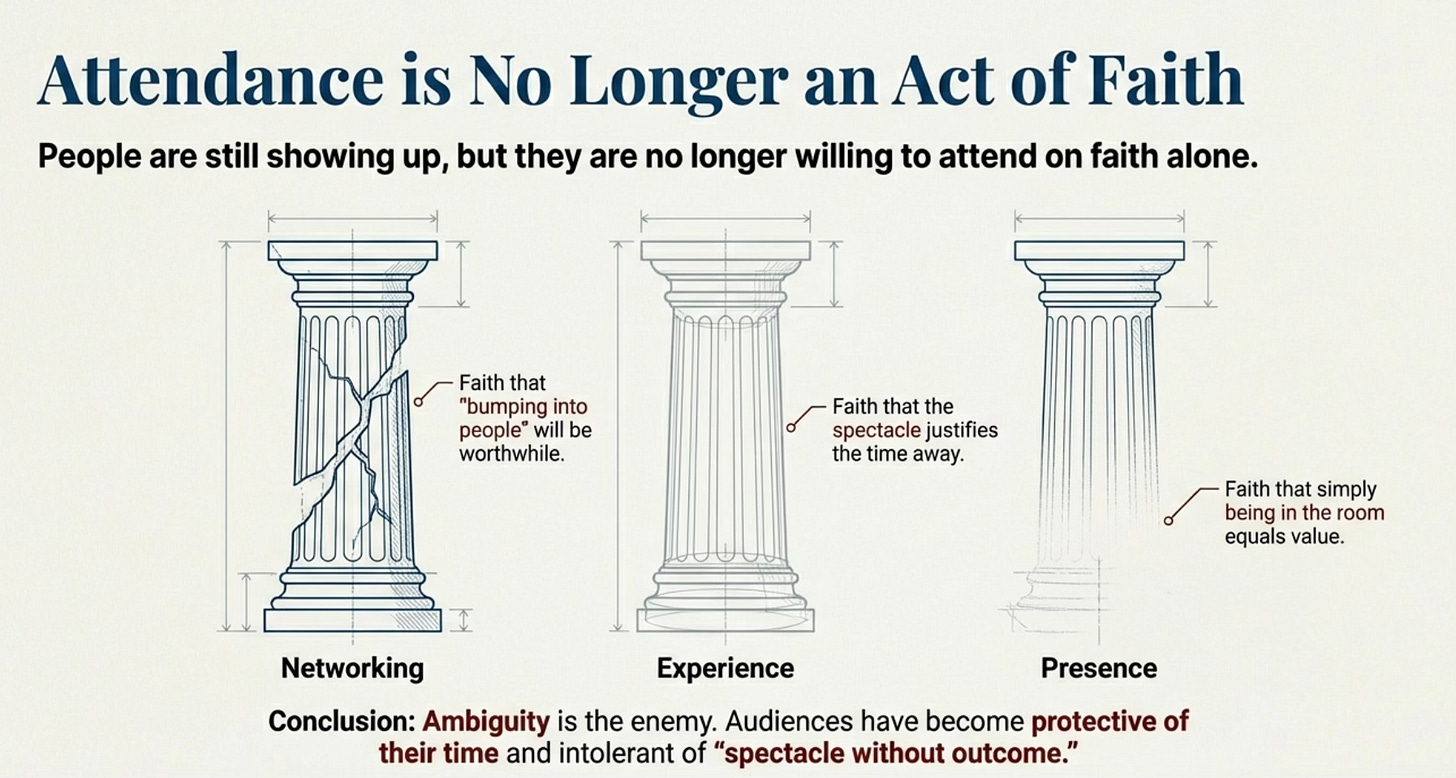

Across attendance behavior, workforce dynamics, and attendee motivation, the data points in the same direction. People are still showing up, but they are no longer willing to attend on faith. Faith that the networking will be worthwhile. Faith that the experience will justify the time. Faith that learning will translate into action. Faith, especially, that presence alone is enough.

It isn’t.

Commerce has overtaken experience as the primary reason people attend events, not because audiences have become transactional, but because they have become protective. In a culture where time feels perpetually scarce, commerce functions as proof that attention was respected.

Networking, once the industry’s most dependable promise, has dulled. People still want connection, but not the theatrical version built on name badges and vague follow-ups. They want context before contact, relevance without performance, and evidence that someone thought carefully about who should actually meet whom.

Experience still matters, but no longer on its own. Beautiful moments amplify meaning; they don’t create it. Experience without consequence now reads as décor—polished, impressive, and oddly hollow.

Beneath these shifts runs a quieter current. Retention, long treated as a secondary metric, has become the real story. Attendance has proven resilient. Loyalty has not. Industry-wide, year-over-year attendee retention now sits around thirty to thirty-five percent, meaning many events are rebuilding their audience annually rather than sustaining it. Full rooms mask fragile continuity.

The reason is as telling as it is uncomfortable. Nearly one in five attendees no longer believes their core objectives—meaningful connection, useful learning, tangible progress—are being met. These are not angry exits. They are silent ones. People come once, recalibrate, and simply don’t return.

What makes this moment different from previous cycles is where the pressure comes from. In the past, retention losses were driven by external forces—budgets, travel, organizational churn. What Freeman’s data captures now is internal recalculation. People are choosing more deliberately where their time goes and are less tolerant of ambiguity, spectacle without outcome, or participation without purpose. Retention becomes a proxy for trust.

Compounding the issue is a parallel workforce shift embedded in the same research. Retirement is outpacing retention inside the industry itself, thinning institutional knowledge as audiences become more exacting. The people with the deepest instincts for pacing and judgment are exiting as the margin for error narrows. The result is a curious fragility: events that are technically competent and emotionally underpowered.

Freeman does not prescribe solutions. That restraint is part of the report’s credibility. But the implication is hard to miss. Retention is no longer a marketing problem. It is a design problem. And design demands authorship.

My take is that at moments like this, it helps to remember that convening has never been neutral. Long before platforms and apps, gatherings were serious acts—establishing norms, creating obligation, shaping identity.

Imagine arriving at a gathering shaped by Confucius. Before you reached the room, you would understand your role. Hierarchy would be legible. Obligation would feel like respect. You would know when to speak, when to listen, and why both mattered.

A gathering designed by Plato would move deliberately from surface to substance, from opinion to principle. Comfort would not be the goal.

Socrates would dispense with speeches altogether, using questions to destabilize certainty. Retention metrics would suffer. Influence would not.

Then there is Benjamin Franklin, whose gatherings were working systems. Ideas were tested against reality, and something tangible was expected to emerge. Commerce was proof that the convening mattered.

And Voltaire would introduce friction on purpose, puncturing false consensus and reminding the room that progress often requires discomfort.

These figures were not remembered because they spoke well. They were remembered because their gatherings worked. Their authority was architectural.

Modern events, in an effort to be inclusive and frictionless, have often stripped away this authorship. The result is something pleasant and forgettable. Freeman’s data shows what happens next. People stop coming back.

What’s emerging now—visible first among entrepreneurs and increasingly within associations—is a re-centering of power away from the keynote and toward the convener. Attendees talk less about who was on stage and more about how the event felt, how the agenda unfolded, how the right people appeared at the right moment. What they are responding to is authorship.

On the entrepreneurial edge, this has long been true. Many of the most compelling events are inseparable from their founders—not as personality brands, but as points of view. The founder’s reputation becomes the container. Meaning cannot be outsourced. Coherence cannot be delegated. Clarity becomes the brand long before the logo does.

Associations are beginning to notice. As the annual meeting becomes the primary expression of institutional value, convening skill starts to look like leadership. The event becomes an audition. Convening becomes a ladder.

The solution hiding in plain sight is not louder marketing or more elaborate spectacle. It is authorship. Someone must own the intent, the arc, the collisions, and the consequences of the gathering. Facilitation—not as stage management, but as cultural stewardship—re-emerges as the defining craft of the next era.

Events will increasingly be judged by a single question on the way out: what changed because I was there?

Freeman’s research gives this moment empirical weight. The conversations give it texture. My wager is that what’s now visible at the edges—founder-conveners, facilitator-led formats, leadership expressed through gathering—will soon become the expectation.

The room hasn’t grown colder. It has grown clearer.

And clarity has a way of reassigning power.

A bonus Song For This Report

Your content today feels exceptionally true. I resonate with it and I find it responds to much of how I look at this industry now. It’s time for big shifts in leadership because not everyone is retiring and frankly, that would really prompt some new practises and outcomes. I feel that the industry skirts the topics to keep themselves safe and drives self-centred decisions to maintain quorum. Maybe it’s truly time to call out what this industry needs less of and respond faster to what we need more of.