How Governments Incentives Are Quietly Rewriting the Global Events Calendar

Incentives, risk-sharing, and infrastructure—not demand alone—are now deciding where conferences and trade shows are launched, scaled, and sustained.

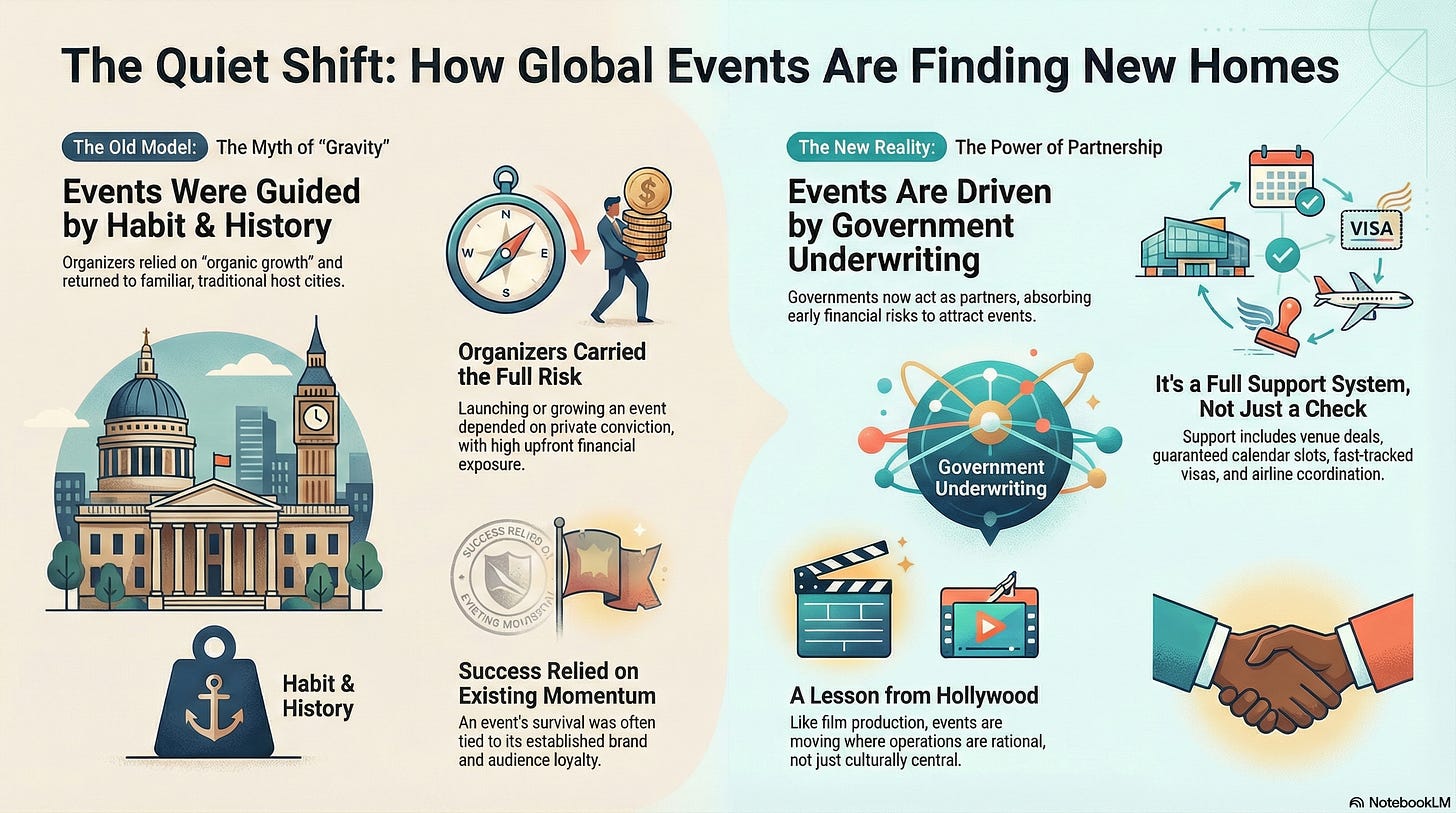

For a long time, the global events industry believed in gravity. Trade shows appeared where they had always appeared, conferences returned to the same cities year after year, and calendars filled themselves as if guided by something natural and uncontested. Organizers spoke of “organic growth” and “natural homes,” borrowing language from biology to avoid admitting how much habit and inheritance were doing the work. It wasn’t dishonest so much as incomplete, a story that held until the cost of pretending it was still true became too high.

What’s changing now isn’t the collapse of familiar centers nor the sudden triumph of new ones, but a quieter redistribution of confidence. Events are moving—rarely announced, never ideological—toward places willing to absorb uncertainty and share early risk. The mechanism isn’t branding or ambition. It’s underwriting, executed with enough discretion that it often goes unnoticed by everyone except the people signing the contracts.

Adam Parry has been watching this long enough to recognize the pattern when it appears. “People talk about incentives like they’re perks,” he says. “They’re not. They’re permission.” Permission to launch something that might take time to find its footing. Permission to survive a first year that’s merely competent. Permission to build instead of endure. His authority on the subject doesn’t come only from years of editorial distance; it comes from proximity. As the founder of Event Tech Live and Event Industry News, he has spent years watching what happens when ideas leave pitch decks and meet rooms, where technology has to perform under pressure and where the margin for error is measured not in clicks but in empty chairs. Over time, patterns emerge—not because anyone predicted them, but because they repeat.

Parry’s perspective has also shifted geographically. He now lives in Dubai, a move that felt less like relocation than alignment after years of traveling through the region and observing how deliberately events were being treated there. From that vantage point, incentives aren’t theoretical constructs; they’re visible in how calmly first editions are launched, how confidently calendars harden, and how little drama surrounds decisions that once required heroic conviction.

The film industry ran this experiment years ago, and its history offers a useful precedent precisely because it unfolded without catastrophe. Hollywood didn’t disappear when productions began shooting in Georgia, Vancouver, Budapest, or the UK. Los Angeles lost volume, not cultural authority, as tax credits, labor rules, and permit certainty made it rational to point cameras elsewhere. The stories were still imagined in the same places; the production schedules simply learned to travel. The brand stayed. The cameras moved. Events are now following a similar path, though with fewer headlines and far more spreadsheets.

In the events world, incentives almost never arrive as a single check. They appear instead as conditions: a destination quietly agreeing to share early losses; a venue removing itself as the largest fixed risk on the balance sheet; a calendar slot guaranteed for three or five years so an organizer can think about building a brand rather than surviving an opening weekend. Government agencies sit on steering committees, not to interfere but to align national priorities and ensure a hall doesn’t empty out before lunch. Airlines block seats before marketing plans are finalized. Visa processes shrink from months to days. Marketing seems to exist everywhere without ever appearing on an invoice. None of this is framed as subsidy. It’s framed as partnership.

The largest organizers understood this long ago. Companies like Informa, RX, and Clarion Events don’t wander into new markets hoping for the best. They arrive after conversations have been had and assumptions agreed, often with governments and quasi-governmental agencies already aligned around economic development, industry signaling, and calendar certainty. Shows don’t “travel.” They’re invited. To outside observers, this looks like momentum. Inside the room, it looks like math.

Germany institutionalized this logic decades ago. The Messe system—organizations such as Messe Frankfurt, Messe München, Koelnmesse, and Deutsche Messe—was never designed to be purely commercial. These were publicly backed entities tasked with attracting global industries and creating long-term trade ecosystems. First editions were treated as investments, not bets. Calendar certainty was assumed. When German shows traveled—Automechanika, Ambiente, Light + Building—they exported not just a brand, but a way of thinking about how risk should be absorbed. What’s happening now elsewhere is not disruption; it’s the globalization of the Messe concept, often faster and with fewer constraints.

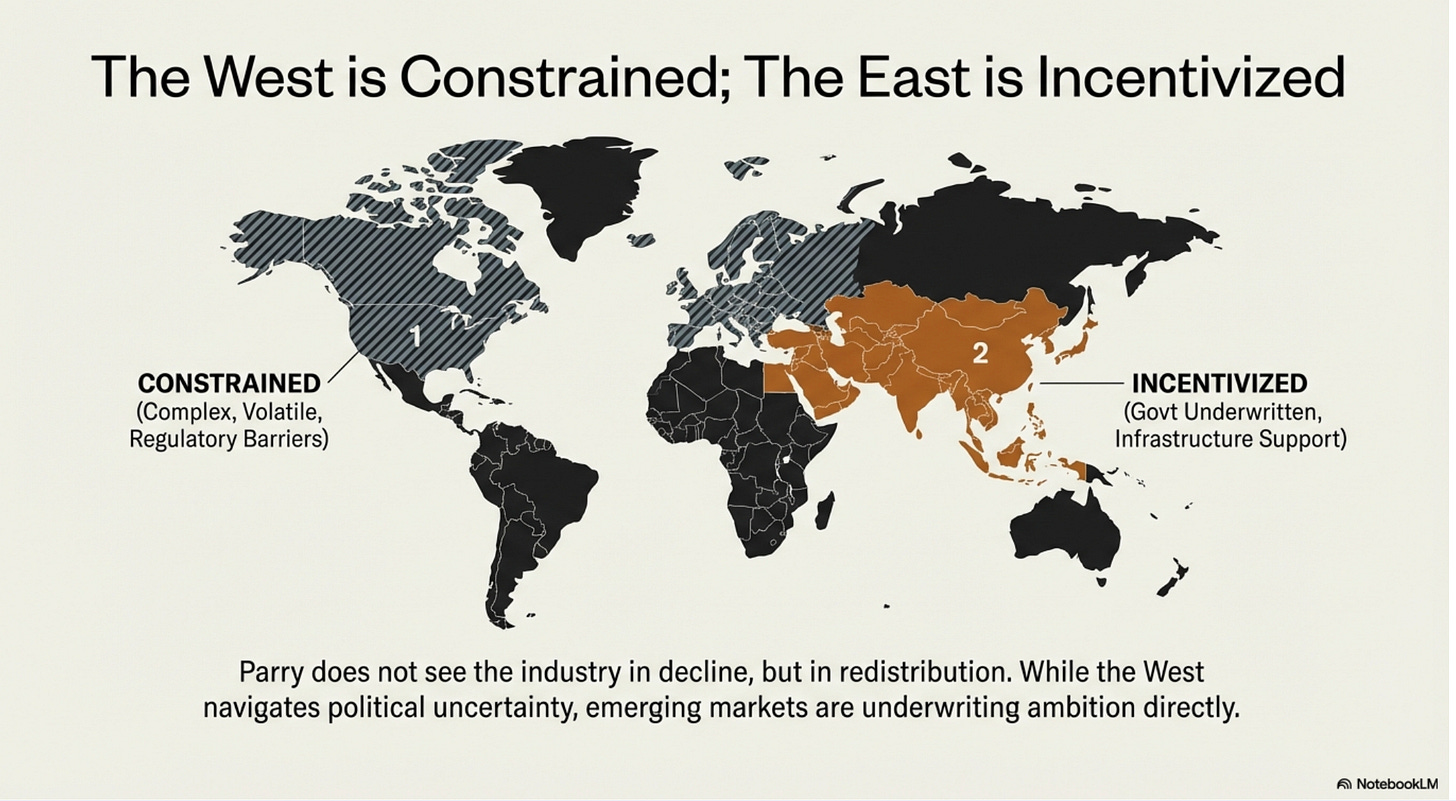

The geography of this shift is broad and deliberate. Across the United Arab Emirates, events are treated as infrastructure, curated rather than chased. Saudi Arabia folds convenings into national transformation strategies, treating them as cultural and economic signals. Qatar deploys events selectively, tying them to diplomacy and soft power. In Singapore, business events have long been procedural, supported by bid underwriting and government advocacy that remove drama from launch decisions. China has for years used exhibitions as industrial policy, often co-owning shows outright, while South Korea and Japan pair advanced infrastructure with quiet state alignment. Europe competes discreetly—Germany anchoring the system, with Spain, Portugal, Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic competing behind closed doors. The United Kingdom, having watched film and television leave and return through tax credits, now faces a similar reckoning in events. In the Americas, the United States remains influential but fragmented, competing city by city, while Canada coordinates more deliberately and Brazil emerges through population gravity once early risk is softened. Across Africa, Rwanda, South Africa, Morocco, and Kenya choose their signals carefully rather than chasing volume.

Vendors understand these dynamics before anyone writes about them. You don’t open a warehouse because a city sounds exciting; you do it because the second and third editions are already assumed. AV companies don’t stage equipment locally on optimism. Registration platforms don’t relocate senior teams for branding. They move because the calendar has hardened. Once vendors arrive, lead times shorten, costs stabilize, rehearsals become possible, and agencies stop designing defensively. Precision returns, not because budgets have exploded, but because time—usually the most expensive luxury in events—has suddenly become affordable again.

What rarely gets credited in these conversations is how deliberately incentives are designed around the person wearing the badge. Organizers talk about underwriting; attendees experience something else entirely. Flights align with event calendars instead of forcing contortions through secondary hubs, often because state-backed airlines have quietly added capacity or stabilized pricing around the dates. Visas stop being acts of faith—fast-tracked, on-arrival, or event-specific waivers turn international attendance into a plan rather than a gamble. Ground transport works without explanation. Hotels understand load-in nights and late finishes. Venues are staffed for surge rather than apology. Signage makes sense. Wi-Fi holds. Safety removes low-grade vigilance—walking at night, carrying equipment, moving between venues without friction. Most importantly, time returns: attendees arrive less depleted, stay longer in sessions, and linger in conversations that would otherwise be cut short by logistics. In places where governments co-own events, access shifts as well—regulators, ministers, and national champions appear not as keynote abstractions but as participants, which for many audiences is the real reason to attend. None of this feels luxurious. It feels intentional. And once attendees experience that level of consideration, their tolerance for anything less recalibrates permanently.

This is where the American question surfaces quietly. If incentives continue to work elsewhere, does the United States risk becoming Hollywood—culturally central, operationally less necessary? History suggests not disappearance but decoupling. Los Angeles still defines film culture. It no longer defines where films are made. The same may be true of events: America will continue to matter for influence, capital, and credibility, but unless risk-sharing becomes systemic rather than local, first editions will learn to travel and mature ones may return.

The danger in all of this is not distortion, as critics sometimes argue, but exclusion—who gets access to these conditions and who doesn’t. When incentives only favor incumbents, consolidation accelerates. When they lower the barrier to experimentation, calendars multiply. That’s the real story unfolding now: not the collapse of a center, but its replication, as more places learn how to make trying possible without making failure fatal.

The center hasn’t collapsed.

It has multiplied.

And once a calendar learns that it can move—quietly, strategically—it rarely returns to believing it was ever fixed in the first place

.