When Jack Morton published its 2026 outlook under the title “Replace Volume With Veracity,” it landed with less fanfare than many industry prediction pieces, and that restraint, intentional or not, was the tell. This was not a document designed to provoke applause or to compete in the annual arms race of trend forecasting. It read instead like something closer to a field report from inside the institution itself, written by an organization that has spent enough time in consequential rooms to recognize when language needs to slow down and meaning needs to thicken.

The word veracity is doing a great deal of work in that title, and it is not doing the kind of work agencies usually ask language to perform. Veracity is not about scale, novelty, or even originality. It is about whether something can be believed, whether it holds together under scrutiny, whether the people in the room feel that what is being staged, said, and implied aligns with what they already know to be true. You reach for that word not when you are chasing attention, but when you are worried about credibility.

Jack Morton has reason to be.

By scale, reach, and historical influence, the firm occupies a singular position in the global events and brand-experience ecosystem. It has been trusted, over decades, with moments that extend well beyond marketing theater, moments when companies needed to align internal cultures, steady external relationships, or project coherence at times when coherence was in short supply. This is not an agency that built its reputation on novelty alone. It built it on the ability to hold rooms together when the stakes were high and the margin for error thin.

That role did not suddenly emerge in 2026. It was clarified under pressure.

During the pandemic, when the familiar architecture of corporate life collapsed almost overnight, many leadership teams discovered something they had not previously articulated. The people inside their organizations who knew how to reach employees, customers, partners, vendors, sponsors, and regulators, often simultaneously and under conditions of extreme uncertainty, were frequently the event professionals. These were the people fluent in constituencies rather than channels, in timing rather than tactics, in the emotional physics of a room rather than the mechanics of a campaign. They understood instinctively that once something is said live it cannot be unsaid, that belief cannot be commanded, and that trust, once lost in public, is almost impossible to restore quietly.

In that moment, events stopped being a department and became something closer to operational glue.

That recognition did not fade when the crisis receded, because the conditions that made it visible did not recede either. Organizations remained distributed. Authority grew noisier. Trust thinned. Attention fractured. And experience, live and embodied, emerged as one of the few remaining places where leadership could appear in three dimensions and be judged accordingly. This is the backdrop against which Jack Morton’s emphasis on veracity begins to make sense.

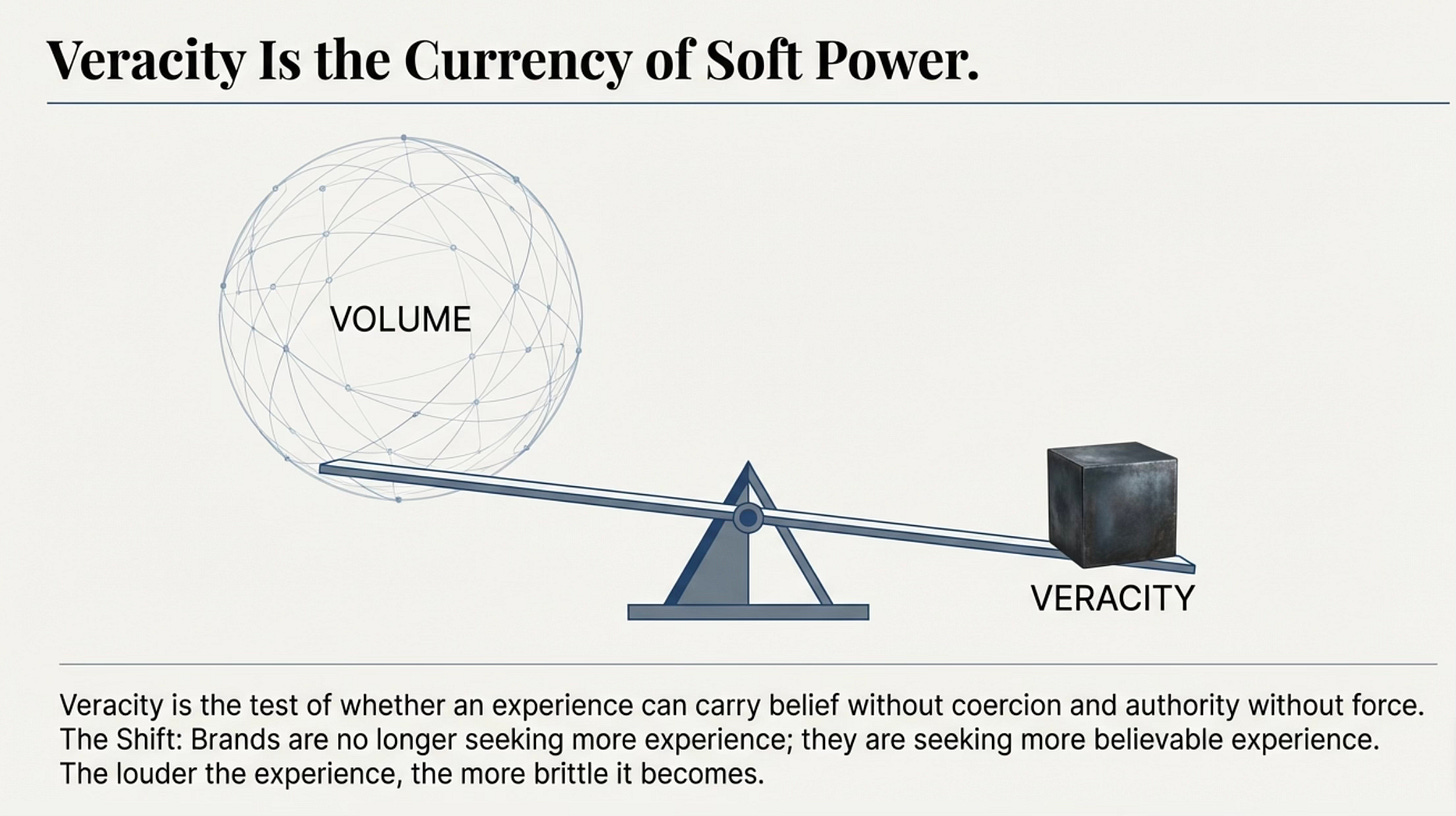

When CEO Craig Millon remarked in The Drum that tariffs had entered client conversations, he was not making an aside about politics or economics. He was describing a structural shift. Experience has crossed out of the marketing sandbox and into the same strategic arena as supply chains, regulation, geopolitics, and reputational risk. In that environment, volume is no longer neutral. The louder the experience, the more brittle it becomes. The grander the promise, the harsher the reckoning if it fails to align with reality.

What brands are seeking now is not more experience, but more believable experience.

There is a deeper lineage here, one that predates experiential marketing as a term and helps explain why Jack Morton, in particular, recognizes this moment for what it is. Long before we spoke about brand experience, there were industrials: large-scale, meticulously choreographed corporate presentations designed not for consumers, but for the people inside the system—sales forces, distributors, regulators, internal leadership. These were not entertainments. They were instruments, built to translate strategy into belief and belief into behavior at moments of transformation. They were blunt by today’s standards, but they were honest about their purpose.

Jack Morton emerged from that world. It learned early that when organizations are changing, people do not follow diagrams. They follow moments. What has changed is not the function of experience, but the environment in which it operates. The room is now public. The audience is more skeptical. Failure travels faster and farther.

This evolution helps explain another part of the story that is easy to miss if you read the 2026 outlook in isolation: the question of ownership. For decades, Jack Morton lived inside the holding-company ecosystem, a structure optimized for scale, integration, and predictability. That model works well for media buying and campaign-based creative. Experience rarely behaves that way. It is labor-intensive, operationally dense, emotionally charged, and deeply cross-functional. As it became more central to the life of organizations—and more exposed to risk—it also became harder to contain inside systems designed for neatness.

The move away from holding-company containment, into a private-equity-backed structure and a merger with Impact XM, feels less like financial maneuvering than structural correction. Experience had outgrown the architecture that once housed it. Other agencies, particularly those working in similarly complex, innovation-heavy disciplines, are making parallel adjustments, stepping out of holding-company logic or being more tightly integrated only where their complexity can be managed. The sorting is underway, even if it has not yet been named as such.

This is where the idea of soft power becomes unavoidable.

I recognize it not as a metaphor, but as a practice, having seen it operate up close in diplomatic settings, including my own experience with the United States Department of State, where influence rarely moves through decree and almost never through volume. At State, power travels through invitation lists, seating charts, protocol, presence, and trust accumulated quietly over time. It is exercised through choreography as much as content, through atmosphere as much as argument. Event professionals have been practicing that same craft inside corporations for years, often without the language to describe it.

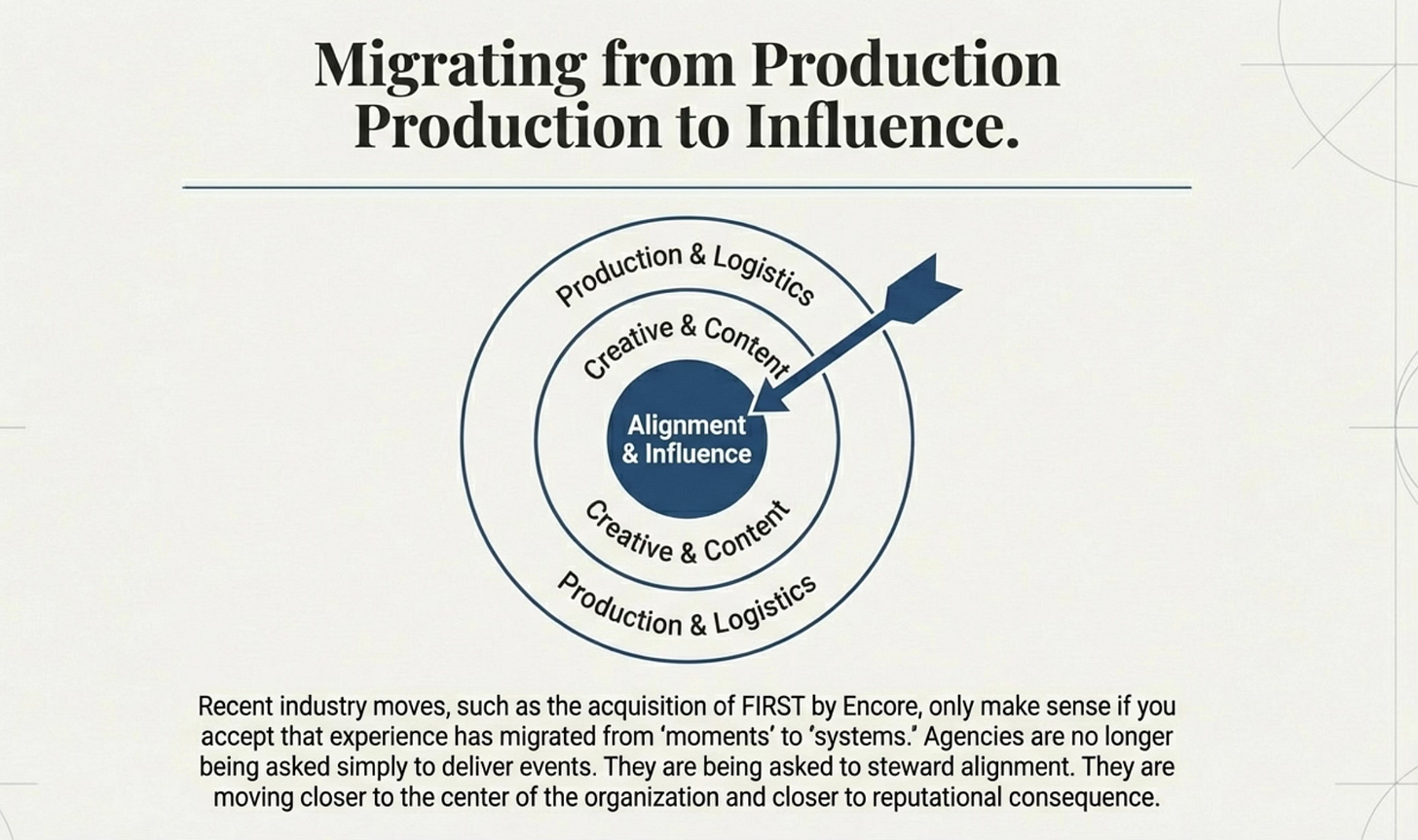

That practice is now being formalized. You can see it in models built around embedding event teams inside organizations, keeping them close to leadership, culture, and consequence rather than parachuting them in episodically. The recent acquisition of FIRST by Encore makes sense only if you accept that experience has migrated from production to influence, from moments to systems. Embedded teams do not just execute events. They accumulate context. They understand when visibility is useful and when restraint carries more authority. They practice soft power daily, informed by proximity and memory rather than briefings alone.

Seen through that lens, the consolidation at the top of the industry begins to look less like a land grab and more like adaptation. Experience is being pulled closer to the center of organizations, closer to leadership, closer to reputational consequence. Agencies are no longer being asked simply to deliver moments. They are being asked to steward alignment.

This is where Jack Morton’s language about veracity finally resolves itself. Veracity, in this context, is not a branding flourish. It is the test of whether an experience can carry belief without coercion, authority without force, influence without theatrics. It is the soft-power equivalent of credibility, earned through consistency, presence, and coherence over time.

Industrials understood this plainly. They knew that when an experience failed, it did not merely disappoint. It misaligned. That lesson never expired. It was simply submerged beneath decades of spectacle.

Read this way, “Replace Volume With Veracity” is not a forecast at all. It is an acknowledgment that the industry has come full circle, back to experience as an instrument of alignment rather than amplification. We have been here before, under different names and conditions, when events carried institutional weight and meaning was not optional.

What feels new now is the visibility. The room is bigger. The audience sharper. The consequences unmistakably public.

And that is the quiet truth sitting underneath Jack Morton’s 2026 outlook, whether the industry is yet comfortable naming it or not: experience has become infrastructure, soft power has become central, and the responsibility of those who design and steward these moments has never been heavier.