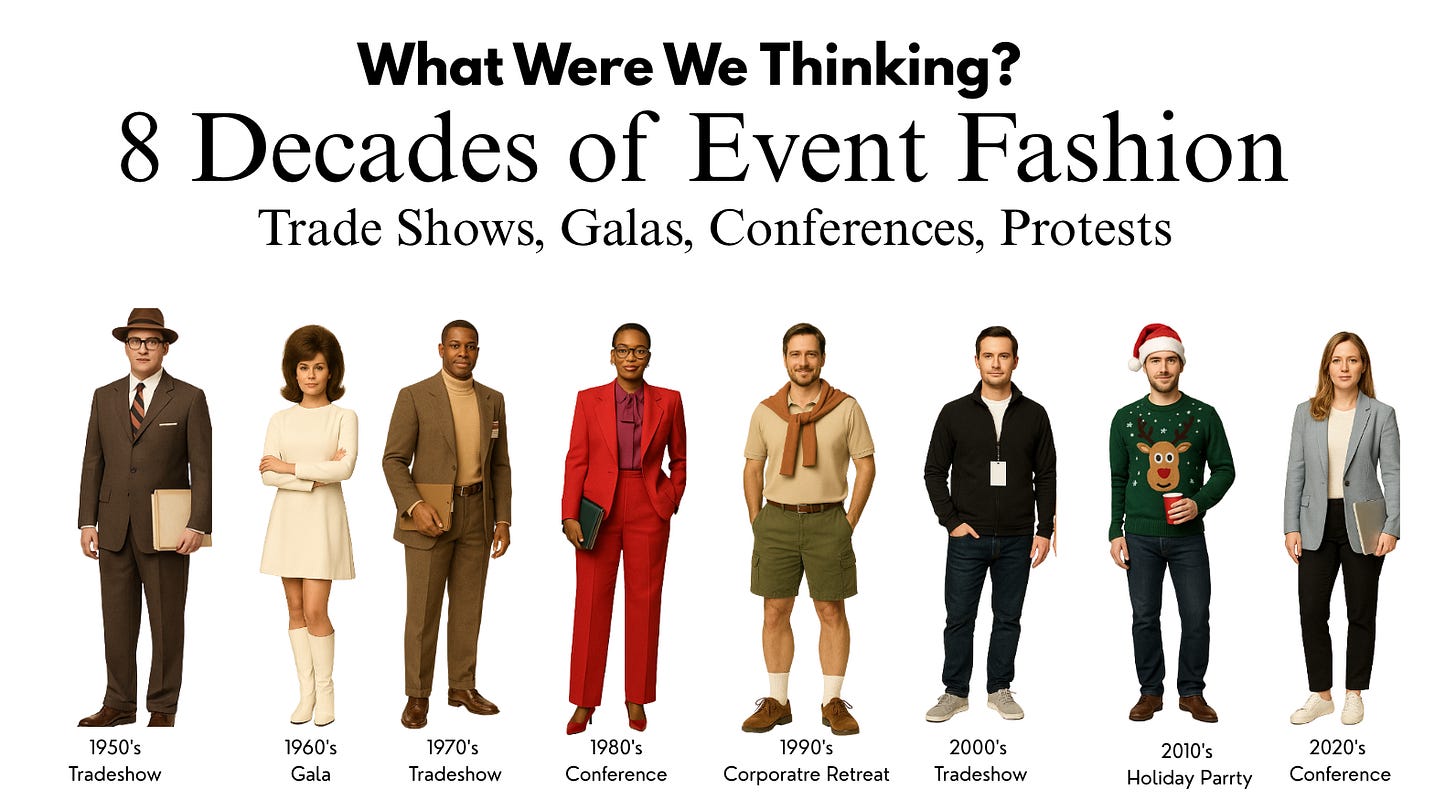

Decoding Event Fashion: Eight Decades of Style, Signal, and Showing Up

From trade show floors to protest marches, wedding aisles to keynote stages—this is a cultural timeline of what we wore to events and why it mattered. Fashion wasn’t just fabric. It was code.

Editor’s Note

While walking through downtown Nantucket this summer, I stepped into the local shoe museum—and it got me thinking: how much of what we wear has been shaped by the places we go, and more specifically, the events we attend?

From trade shows to protests, galas to conferences, the events industry doesn’t just host culture—it dresses it. For better or worse, we’ve helped define what it means to show up. Sometimes it’s elegant, sometimes it’s absurd. But it’s always a signal.

So we built a timeline of how we’ve dressed to gather—decade by decade. Scroll through, take it in, and ask yourself:

Which era feels most like you? Which one made you laugh—or cringe?

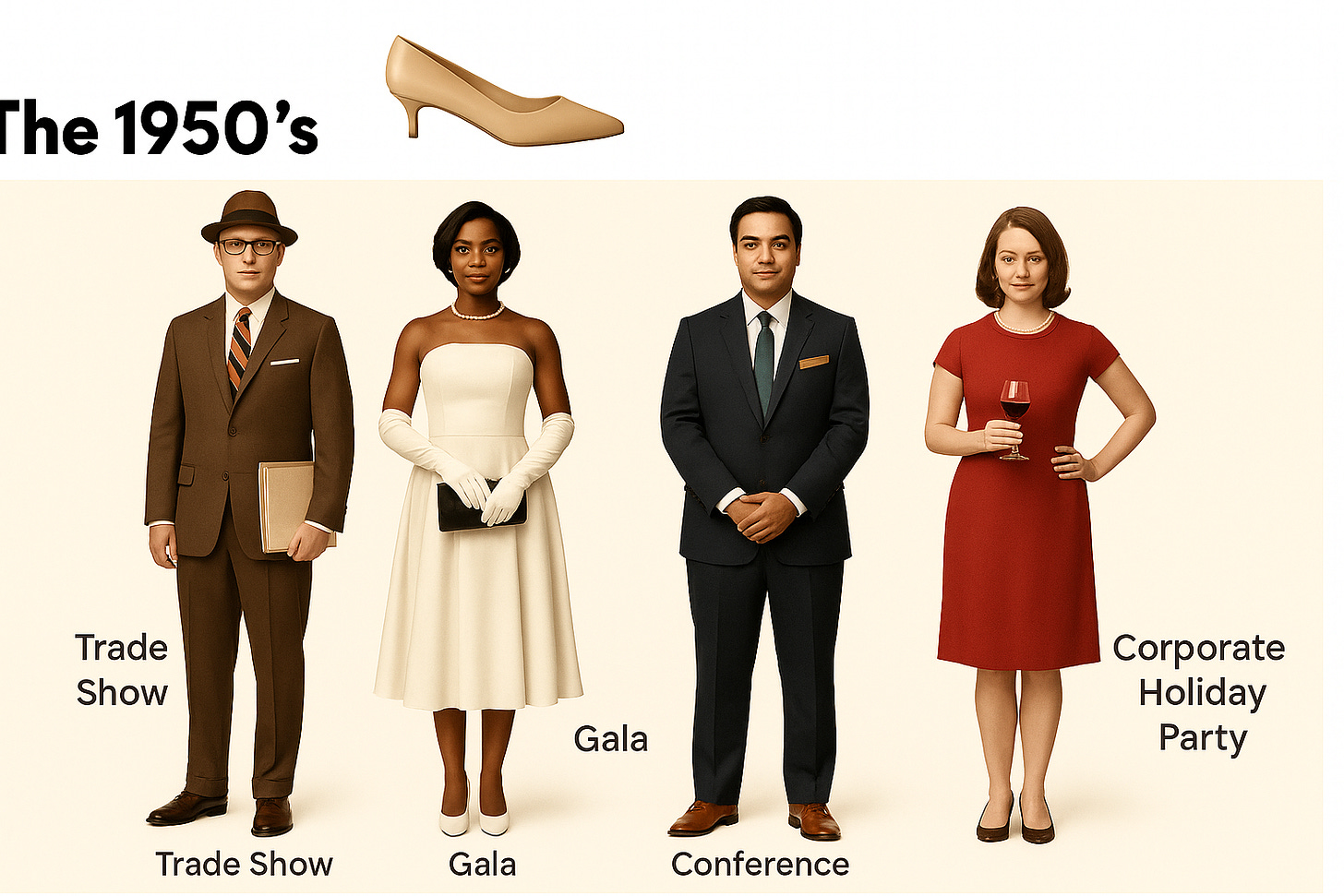

The 1950s: Corporate Charm, Suburban Glam, and the Code of Conformity

The 1950s arrived starched and structured. After the war’s austerity, people embraced rules—not just in politics and pop culture, but in what they wore to gather. Fashion at events became codified, codified became culture, and culture became conformity. To attend a trade show, a debutante ball, a chamber of commerce luncheon, or even a school fundraiser, you dressed the part—and that part came with a blueprint.

At trade expos and professional conferences, men wore charcoal suits with narrow ties and neatly folded pocket squares. Women—who were increasingly present as administrative leads and product demonstrators—dressed in matching two-piece skirt sets, kitten heels, and “company colors” lipstick. You could walk a convention floor and know the brand by the silhouette alone.

In the social sphere, fashion reflected the suburban ideal. Cocktail dresses with cinched waists, opera gloves, and pearls at fundraising events. Tuxedos for galas. Seersucker for garden parties. Weddings were formal by default. Even informalgatherings had a kind of practiced elegance—hairstyles were set, nylons worn even in heat, and shoes shined to military precision.

Public events—parades, political fundraisers, victory anniversaries—often felt like walking catalog spreads. Families lined the streets in Sunday-best apparel, and civic pageants reinforced the idea that presentation was patriotism. Fashion said you were good, decent, and belonged.

But underneath the sheen, the first cracks were showing. Beatniks started showing up in black. Young women rebelled with slimmer silhouettes and shorter hems. It would take another decade for the revolution to arrive—but it started here, with small acts of stylish defiance beneath the polished surface.

Signature Shoe: The kitten heel pump. Understated, dainty, and respectable. Worn by office secretaries, gala guests, and convention presenters alike

Defining Events:

– The 1955 American Management Association Conference, where every man wore a hat and every woman brought her own notepad—and neither dared wrinkle their suit.

– The Junior League Spring Gala, a sea of tulle, pastel gloves, and waistlines you could set a clock to.

– The 1953 Eisenhower Inaugural Parade, where crowds wore their Sunday best and suburban fathers matched their sons in structured overcoats and optimism.

Dress Code Lesson: In the 1950s, to dress for an event was to comply—with tradition, with gender roles, with societal expectations. Your outfit didn’t just reflect taste. It confirmed your place.

The 1960’s: Mod Meets Marching Orders

In the 1960s, event fashion fractured—deliberately. There was no longer a single uniform for showing up. How you dressed to gather depended on what you believed in. The gala scene still shimmered with the last of Eisenhower-era elegance, but just blocks away, marches, salons, summits, and sit-ins signaled a sartorial rebellion that rewrote the dress code for a generation.

At conferences and trade shows, men still wore suits—but narrower now, sleeker. Lapels shrank, ties slimmed, and hair got longer as the decade wore on. Women began to infiltrate business spaces in mod silhouettes—bold geometric prints, miniskirts, opaque tights, and patent leather flats. Booth hostesses wore go-go boots and color-blocked tunics. Progress had a pattern, and it popped.

At protests and parades, fashion became politics. From the March on Washington to Vietnam War demonstrations, young people showed up in trench coats, denim jackets, work shirts, army surplus, and dashikis. Hair was longer. Messages were literal—T-shirts and pins declaring opposition to war, segregation, and the establishment. Dressing for a public event was no longer about blending in. It was about standing out—together.

Galas and social functions told a different story. Jacqueline Kennedy set the tone: pillbox hats, bouffants, pastel suits, opera gloves. White House dinners, charity balls, and international summits still required an ultra-curated refinement. But the youth weren’t interested. They were busy throwing avant-garde happenings in abandoned lofts, wearing vintage slips and bare feet.

The 1960s was the first era where what you wore to an event was a conscious declaration of which side you were on—even if the event was a product launch or a state dinner. The look wasn’t just style. It was strategy.

Signature Shoe: The white go-go boot. Worn at product launches, pop art parties, and on protest lines. Bold, clean, futuristic—and built for walking into the next decade

Defining Events:

– The March on Washington, 1963: Church suits, trench coats, and quiet dignity styled as solidarity.

– IBM Systems/360 Trade Show Debut, 1964: Corporate modernism in action—shift dresses for women, navy suits for men, every badge worn with pride.

– Andy Warhol’s “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” parties, 1966–67: Silver wigs, vinyl jackets, thrift-store chic turned conceptual statement.

Dress Code Lesson: The 1960s shattered uniformity. To dress for an event meant to take a stand—on race, war, gender, art, or identity. Whether you wore a suit or a slogan, it said something. Gathering had become political. Fashion made it personal.

The 1970s: Velvet, Vision, and Booth-to-Disco Dressing

By the 1970s, event fashion had learned to loosen up—without losing intention. Polyester replaced wool. Fringe replaced restraint. And the dress code no longer cared whether you were at a gala or a trade show, a protest or a political dinner. You still dressed to gather, but you dressed like you meant to be seen.

At consumer expos and industry trade fairs, salesmen showed up in wide-lapel suits, flare pants, and sideburns to match. Women working booths often wore color-blocked uniforms—mini-shift dresses with piping and knee-high boots that were part Pan Am fantasy, part office cosplay. Overhead fluorescents flickered on glossy brochures and even glossier fabrics. If you weren’t shimmering, were you even exhibiting?

On the protest circuit, fashion took a radical turn—denim jackets with embroidered slogans, suede fringe worn like armor, and the first signs of T-shirt typography culture. At feminist salons and consciousness-raising gatherings, you might find one attendee in an earth-toned knit dress and another in a military surplus coat. The statement wasn’t what you wore—it was how you showed up in it.

Meanwhile, the gala scene split in two: one half still clung to taffeta and shoulder wraps, while the other embraced full Studio 54 glam. Sequins on socialites, metallic halters on heiresses, and velvet suits at foundation dinners signaled that luxury had a new language—and it had a disco beat.

Signature Shoe: The platform heel. Towering, expressive, and often dangerous. Worn on trade show floors, gala dance floors, and protest marches alike—with equal parts flair and risk.

Defining Events:

– The 1976 Bicentennial Trade Expo, where America’s future was sold in booths staffed by polyester-clad optimism.

– Studio 54 Fundraiser Galas, where city elites and pop icons danced in Lamé and Lurex, under the guise of philanthropy.

– The Equal Rights Amendment Marches, where slogan tees met suede fringe and aviator shades on a sea of determined silhouettes.

Dress Code Lesson: In the 1970s, fashion at events became emotional armor—part performance, part protest. You dressed to shimmer, to stand out, to take up space. And whether you were pitching a product or a cause, you walked in like the outfit had something to say.

The 1980s: Suits, Sequins, and the Armor of Intent

No decade better captured the power of dressing to project than the 1980s. The events industry ballooned—mega-galas, exploding trade shows, globe-trotting corporate conferences—and the dress code followed suit, literally. Whether you were storming the expo floor in Anaheim or making a political statement at a die-in on Fifth Avenue, what you wore was strategic.

At the National Hardware Show, shoulder pads turned up in both genders. Women entered the booth wars in business armor—bow blouses and skirt suits designed for deals, not flirtation. Meanwhile, on the fundraising circuit, sequins and metallics screamed wealth louder than words. Event planners coined new rules—black tie with “festive flair,” or “business attire, no jeans,” a phrase born in this era.

But fashion wasn’t all flash. Protest events—especially in the AIDS activist movement—rewrote the visual grammar. A slogan T-shirt and combat boots at an ACT UP demonstration outside the FDA wasn’t underdressed. It was precision messaging.

Signature Shoe: For the boardroom-bound: Ferragamo pumps or tasseled loafers. For the radical: Converse, Docs, or custom-painted boots that could survive both a march and a dance floor.

Defining Events:

– The 1985 National Association of Broadcasters Convention in Las Vegas, where pastel pantsuits networked over beige carpeting and pagers.

– The ACT UP Wall Street Protest, where dressing down was the sharpest tactic.

– The White House Correspondents’ Dinner, 1988 edition—where gowns and gossip collided in a sea of Reagan-era self-congratulation.

Dress Code Lesson: The 1980s was a high-stakes game of first impressions. Whether you were selling, resisting, or fundraising, the right outfit was your pitch deck, protest sign, or power statement.

The 1990s: Casual Fridays, Corporate Cool, and the Anti-Style Statement

The 1990s were a strange cocktail of ambition and ambivalence. Events still demanded polish, but the formality of decades past began to fray at the seams—sometimes literally. You could walk into a major tech trade show in a blazer and jeans or attend a high-society gala where minimalist Calvin Klein had replaced beaded ballgowns. The dress code was shifting, even if no one had officially rewritten it.

At Internet World in 1998, lanyards were the new neckties and Steve Jobs’ black turtleneck quietly dethroned the three-piece suit. Meanwhile, corporate retreats and off-sites flirted with fleece—Patagonia vests replacing dinner jackets as power signals in VC circles. And yet, elsewhere, formality still held its grip. The White House Correspondents’ Dinnerremained a black-tie press prom, and major weddings or museum galas kept dry cleaning in business.

On the streets, fashion-as-protest returned with quiet fury. Million Man March attendees dressed in dignified, church-adjacent attire—signaling pride, unity, and formality as power. In contrast, anti-globalization rallies (like Seattle WTO, 1999) saw anarchist black-blocks in tactical boots, balaclavas, and modified thrift.

Signature Shoe: The square-toed slip-on (for every mid-level exec), or the chunky-soled Steve Madden platform worn to concerts and dot-com launch parties. Sneakers began creeping into conference culture—subtly, then proudly.

Defining Events:

– Macworld 1997: Steve Jobs’ return to Apple, marking the dawn of the “CEO uniform” revolution.

– The Million Woman March, 1997: Where eventwear became soulwear—button-downs, headwraps, and empowerment through presence.

– Internet World Expo, 1998: A sea of khakis and branded polos—corporate cosplay for the coming Web 1.0 boom.

Dress Code Lesson: In the 1990s, rebellion dressed down and leadership did, too. Dress codes started bending—until they no longer held.

The 2000s: Branded Casual, Fleece Credentials, and Post-9/11 Minimalism

The 2000s dressed down—strategically. Formality lost ground to identity, and the new event dress code was “startup serious.” You didn’t show up in a suit unless you were losing. At galas, CEOs wore black tie. But at everything else, they wore hoodies.

At conferences and trade shows, badge culture bloomed. Eventwear became about functionality plus optics. At Dreamforce, CES, and TED, lanyards and messenger bags marked insider status. Attendees wore branded zip-ups, minimalist tech gear, and business sneakers. The uniform said: I belong here, and I’m building something.

At political events and protests, clothing was emotional camouflage. Post-9/11 fundraisers often called for subdued black, like a civic dress rehearsal for grief. The Code Pink movement introduced intentional irony: pink boas, dresses, and hand-painted signs deployed as protest theater. The color was the message.

In the social realm, weddings and galas straddled two worlds. You had traditionalists in strapless gowns and satin vests. And you had the new minimalists: Vera Wang in soft neutrals, destination weddings in linen, rooftop events with dress codes like “downtown formal.” High style became lowercase.

This was the decade that dressed for comfort, affiliation, and projection. Your event outfit didn’t just match the moment—it matched your mission.

Signature Shoe: The conference sneaker. Think early Nike Frees, Pumas, or New Balances—paired with a logo tee and zip-up vest. Alternately: designer heels with dark-wash jeans and a Bluetooth earpiece.

Defining Events:

– Dreamforce, 2007: The birth of tech-conference casual. A hundred thousand zip-up jackets can’t be wrong.

– Code Pink Anti-War Protests: Protestwear as costume—strategic femininity in pink and pearls.

– Vanity Fair Oscar Party, 2005–2009: The last glittering gasp of Hollywood glam before social media turned fashion into content.

Dress Code Lesson: In the 2000s, you dressed for where you were going—but also for who you might run into. Fashion became visual shorthand for credibility, ideology, and intent.

The 2010s: The Era of the Self-Branded Guest

This was the decade when the guest became the brand. Dress codes didn’t disappear—they multiplied. Black tie still reigned at galas, but suddenly so did “festival formal,” “tech casual,” “Instagrammable,” and the utterly chaotic “come as you are (but look amazing).” The rise of social media meant every outfit might be posted, tagged, or judged—so people dressed not just for the room, but for the feed.

At TED Conferences, the uniform was calculated intellectual casual: clean sneakers, blazers with T-shirts, dresses that moved well on camera. At Art Basel Miami, everything shimmered—linen, lamé, and leisurewear curated to say, “I collect, but I don’t try.” And at political protests, the pink pussyhat became the most instantly viral fashion statement of the decade—crowdsourcing a unified, wearable message in real time.

Meanwhile, weddings and galas entered their Pinterest era. Outfits weren’t just chosen—they were mood-boarded. Guests were told what to wear in palettes and themes. Formality was still valued, but increasingly filtered through “your personality, elevated.”

Signature Shoe: The white minimalist sneaker—Common Projects, Stan Smiths, or Allbirds. Worn to conferences, weddings, and stage presentations alike.

Defining Events:

– Women’s March, 2017: The birth of the protest accessory economy—hats, shirts, pins, capes.

– SXSW 2013–2019: Where startup founders wore logo tees under blazers and called it keynote-ready.

– The Royal Wedding of Meghan and Harry, 2018: Global style diplomacy—every guest dressed as a diplomatic gesture.

Dress Code Lesson: In the 2010s, what you wore said: “I get the memo, but I remix it.” The code was curated individuality.

The 2020s: Paradox, Protest, and the Age of the Fashion Remix

If previous decades had rules, the 2020s burned the rulebook—and stitched something new from the ashes. The only dress code now? Know the context, and break the code with purpose.

At events of every kind, fashion became paradoxical. Corporate conferences saw millionaires in Allbirds. Global summits saw speakers in biodegradable couture. Climate activists wore sculptural upcycled denim while calling out the industry that made it. You might show up to a panel in Balenciaga—or in hiking boots and a branded cap. The look wasn’t fixed. It was fluent.

Protests and rallies became fully theatrical. Garment choices were designed for virality: outfits built to be photographed, clipped, and shared. Queer marches, climate sit-ins, reproductive rights rallies—each had their visual signature. Rainbow cloaks. Body paint. Choir robes. The protest wasn’t just a message. It was a runway.

At the ultra-high-end of event culture, galas embraced fashion as performance art. The Met Gala stopped pretending to be about fundraising and leaned fully into fantasy. But so did decentralized culture: Burning Man outfits rivaled fashion week. TikTok creators launched microtrends from retreat centers in Tulum. Everyone had a look. Everyone had a niche.

Most importantly, the 2020s blurred the line between real and rendered. Digital outfits. AI-generated dresses. Virtual try-ons. Fashion’s role in event design became a creative layer, a brand asset, and a sensory tool.

Signature Shoe: A tie between Crocs-in-tuxedos and Balenciaga sneakers that cost more than your speaker fee. Or better yet: holographic platforms rendered by your AI stylist.

Defining Events:

– Climate Week NYC, 2023–24: Where the dress code went eco-elevated. Garments as activism.

– WEF Davos: Fleece vests, $900 sneakers, and performative humility at altitude.

– The Met Gala, post-2021: Where the fashion was louder than the event itself.

Dress Code Lesson: In the 2020s, what you wear is never neutral. It’s a story, a stance, a projection. Dress codes didn’t just fragment—they exploded into a million micro-signals. In this era, you are the event.