David Allison and the New Values of Events

Why gatherings are being redefined by values, not scale—and what that means for how people show up.

There is a subtle change happening inside gatherings that many organizers can feel but haven’t yet named. Rooms that once hummed with easy momentum now feel more delicate. Audiences arrive informed, alert, and quietly selective. The ballroom is full, the speakers are credible, the agenda has been refined again and again—and yet the collective attention doesn’t automatically cohere the way it once did. Phones appear sooner. Conversations hover politely. What used to feel like chemistry now feels closer to choreography.

The industry has largely interpreted this as a problem to solve: declining attention spans, rising expectations, the need for sharper content or more immersive formats. But that explanation misses something more fundamental. People haven’t stopped caring about gatherings. They’ve started valuing them differently. What’s shifting isn’t appetite, but tolerance—particularly for environments that require performance without purpose.

This is the quiet context in which a new way of thinking about events is emerging, one that doesn’t begin with scale, spectacle, or even engagement metrics, but with a simpler and more demanding question: what makes people feel safe enough to actually arrive?

That question sits at the center of the work of David Allison, who has spent the last fifteen years challenging one of the events industry’s most durable assumptions—that understanding who people are is the same as understanding why they decide to show up, lean in, or return. Demographics describe surfaces. Titles, generations, income bands, and personas are tidy and reassuring, but they explain almost nothing about what makes a room feel credible, meaningful, or worth committing to. Human beings, Allison argues, do not decide based on identity. They decide based on values—the internal filters through which every choice is quietly tested, often without conscious awareness.

Allison is the founder of Valuegraphics, the first research company built entirely around measuring core human values rather than demographics or psychographics. Over the past decade and a half, Valuegraphics has assembled what is now the world’s largest database of human values, drawn from more than a million surveys conducted across 180 countries and 152 languages. The work did not begin as an events thesis. It emerged from frustration. In his earlier career in marketing, Allison watched clients spend extraordinary sums trying to persuade carefully defined audiences to behave in predictable ways, only to see reality refuse to cooperate. Some people responded. Many did not. And then there were always others—people who didn’t resemble the target audience at all—who behaved exactly as hoped.

“We were defining audiences very carefully,” he recalls, “and reality kept ignoring us.”

Demographics, Allison explains, account for roughly ten percent of human behavior. Psychographics, which track preferences and past actions, do a bit better, but they remain backward-looking by design, describing what has already happened rather than illuminating what might happen next. Events, by contrast, are inherently forward-facing. They exist to shape future behavior—to build trust, prompt commitment, and create conditions where people choose to engage rather than withdraw. Neurologically, those decisions are values-driven. When an experience aligns with what matters most to someone, the brain rewards it with dopamine; when it doesn’t, friction appears, even if the surface experience is flawless. This is why two people can sit side by side at the same conference and leave with entirely different impressions, and why so many events feel competent but strangely hollow.

Long before Allison had language for any of this, he had instinct. He grew up in a conventional household in a small city in the Canadian Midwest, a place where expectations were clear and deviation was noticed. As a gay child, he learned early that belonging was conditional. Certain instincts had to be muted, certain values kept private, safety dependent on constant calibration. What emerged was a kind of protective coating—a heightened sensitivity to rooms, to power, to the subtle signals that indicated what was rewarded and what was risky. He became adept at reading people not because he aspired to insight, but because it was necessary.

Storytelling offered both refuge and control. In choirs and school productions, debate club, and as editor of the yearbook, Allison discovered that narrative could shape a room rather than merely respond to it. Performance, in that context, was not about attention so much as agency. But performance carries a cost. For many gay kids, Allison notes, the distance between who you are and who you are allowed to be eventually becomes unbearable. You are not living your values; you are managing them. The self-protection required to survive eventually becomes unsustainable.

With time comes reckoning. Allison often reaches for a line from David Bowie that still resonates deeply with him: Getting older is the magical process of becoming who you should have been in the first place. That realization—that values are not preferences or personality traits but the core of authenticity itself—did not arrive as theory. It arrived as relief.

This is where Allison’s personal history becomes operationally useful for event organizers. Authenticity, as it is often discussed in the industry, is treated like an aesthetic—casual stages, informal language, engineered vulnerability. Allison’s work suggests something far simpler and far more demanding. Authenticity is not self-expression or oversharing. It is the relief of no longer having to hide what matters to you. When environments feel unsafe—emotionally, intellectually, culturally—people perform. They nod, network, and stay agreeable not because they are disengaged, but because they are protecting themselves. Events operate the same way. When a gathering amplifies values that do not belong to the people in the room, participation becomes theatrical. When it reflects the values people already hold, attention deepens, defenses drop, and the room settles into itself. Great events do not make people authentic. They make authenticity safe.

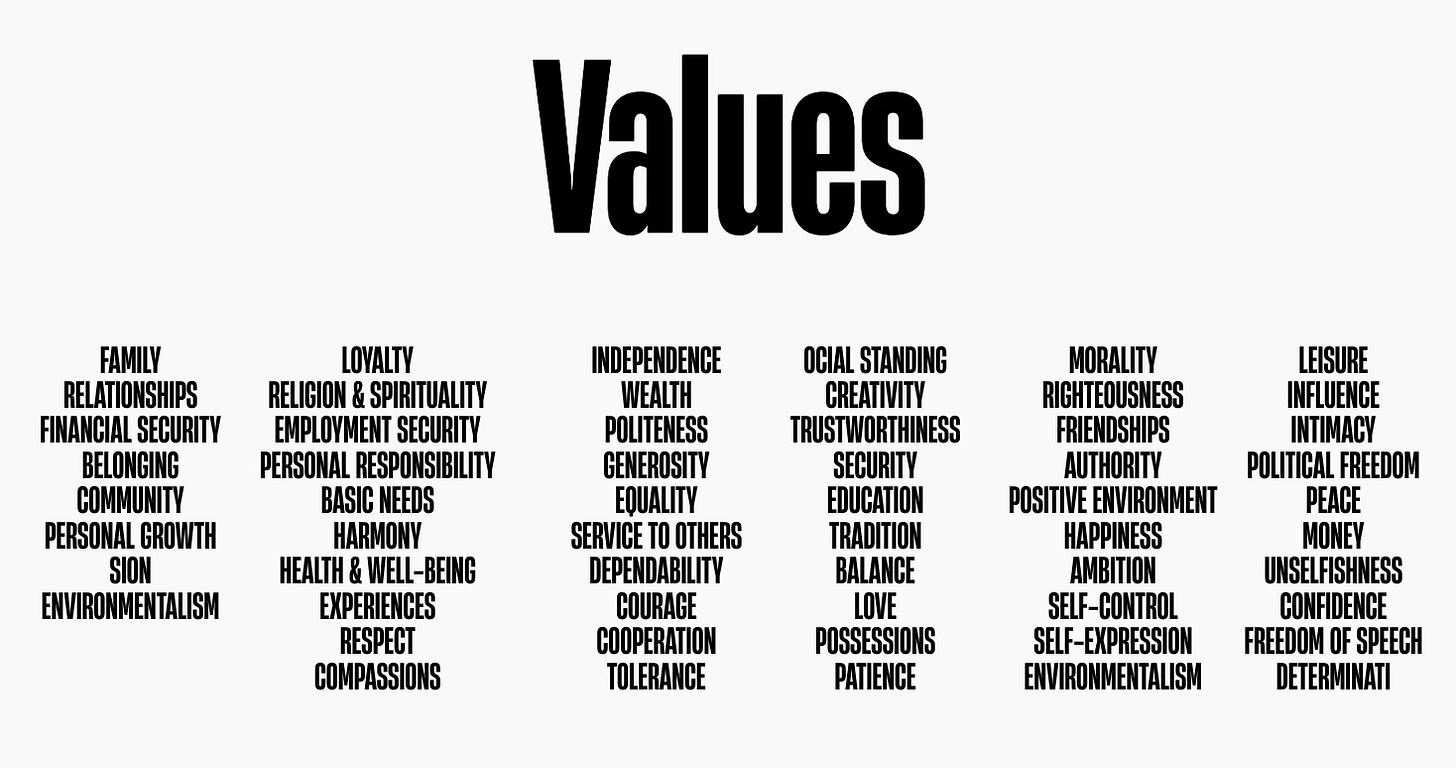

Allison’s framework identifies fifty-six core human values—enduring drivers such as Personal Responsibility, Security, Belonging, Freedom, Creativity and Meaning. These values do not change over time. What changes, and what most organizers fail to grasp, is how differently they are defined. Belonging, for example—the most frequently cited value in the United States—has 912 distinct expressions. Some people feel it when everyone in the room knows their name. Others only when the most powerful person does. Others when the environment signals competence, seriousness, or shared purpose. The value is the same; the implications could not be more different.

Allison often illustrates this precision gap with a scene that feels uncomfortably familiar to seasoned organizers. Picture a plenary session with two thousand people filing in from the back of a ballroom while the CEO and senior leadership cluster at the front table, or disappear backstage until it is time to appear. If the audience’s dominant expression of belonging is being recognized by the most important person in the room, the signal is wrong before a word is spoken. The solution is not theatrical but positional. Put the CEO at the door. Let them greet people as they arrive. A handshake, a name remembered, a brief moment of recognition. For that audience, belonging clicks into place instantly—not because the event is warmer, but because it is accurate. And if that is not the audience’s definition of belonging, Allison notes, “you could station the CEO, the Pope, and the King at the entrance and nothing would change”. Same value. Completely different outcome.

This logic moved from theory to practice when Lori Anderson, CEO of the International Sign Association, heard Allison speak at an ASAE gathering. Her organization’s annual Sign Expo already drew roughly 20,000 attendees and was considered successful by conventional measures. Attendance was strong. Satisfaction scores were fine. And yet something felt incomplete. Her question was simple and practical: could this way of thinking work for their show?

What followed was not a rebrand or a reinvention, but a diagnostic. Allison’s team studied not only attendees, but people in the industry who were not attending and should have been. A small sample answered a short series of questions—not about satisfaction, but about what made experiences feel worthwhile or frustrating. Those responses were mapped against the values database, producing not abstraction but specificity: which values this audience shared, which definitions mattered, and which familiar gestures were quietly undermining engagement. Every touchpoint was examined—marketing language, registration flow, sense of arrival, leadership visibility, session structure, networking design, even pacing and hospitality—through a single lens: did this signal what mattered to the people in the room? The result was not louder or trendier, but quieter and more accurate. Attendees left with an unusually definitive reaction. There was nothing they wanted changed.

When Allison later suggested that I take the same values assessment, the results clarified something I had sensed for years but never articulated. I am not especially drawn to gatherings that promise belonging through informality or manufactured warmth. What consistently works for me are environments that signal responsibility, preparedness, and trust—rooms where people arrive knowing why they are there and respect the seriousness of the exchange. When those signals are present, I engage instinctively. When they are absent, no amount of charm or production compensates. Seeing that preference reflected back was not surprising. It was explanatory. It helped me understand why certain conferences and leadership gatherings feel immediately credible, while others, however well intentioned, feel misaligned. That distinction is the point. Values do not describe who we are. They explain what works on us.

Allison’s ideas have traveled less through white papers than through rooms. His keynotes—delivered at gatherings including IMEX, PCMA, MPI, and ASAE—tend to land not as inspiration, but as recognition. What resonates with organizers is not novelty but relief: the relief of realizing that disengagement is not apathy, but misalignment, and that the solution is not more spectacle, but more accuracy.

What Allison is ultimately pointing to is a revaluation of events themselves. Gatherings are no longer judged primarily by scale, spectacle, or even satisfaction scores, but by something subtler and more enduring: whether they allow people to arrive without armor. In that sense, the new value of events is not energy or entertainment, but alignment. When gatherings get that right, they do more than engage audiences. They earn trust. And in a culture exhausted by performance, that may be the most valuable outcome events can offer.

GatheringPoint Note: Following the Work

For readers who want to explore these ideas more directly, David Allison is the founder of Valuegraphics, whose research focuses on measuring core human values and how they drive decision-making, engagement, and participation across cultures and industries. Allison’s work is increasingly resonant with event organizers because it treats gatherings not as content containers, but as decision environments—places where alignment, safety, and meaning either take hold or quietly collapse.

Wow, David, thank you for such a great article. 😊 If anyone is interested in more specifics, there is a free report on my webpage about the shared values of event attendees and what matters most to them. It's for ALL attendees across the USA, so it's very, very broad, but it's a start! www.davidallisoninc.com/resources