Combating Lookism and the Rooms That Still Sort Us

Even as events lead the way in representation, aesthetic bias continues to shape who gets approached, believed, and remembered inside the gathering economy.

Listen to the Notebook LM analysis

You don’t expect a cultural thesis to arrive on a perfect Nantucket afternoon, certainly not while sitting on a porch where the air feels calibrated for clarity and the Atlantic quietly edits your thoughts. But that was where it began. My friend Christopher Mario—once a sharp-edged journalist, later a philanthropist, and always, unapologetically, a right-of-center thinker—turned to me and asked, with a seriousness that cut through the ease of the day, “David, have you ever really looked into lookism?” It surprised me, not because Christopher avoided complicated ideas, but because this wasn’t the kind of bias people assumed he cared about. I admitted I hadn’t gone much deeper than the dictionary sense of the word. He smiled, half invitation and half challenge, and began an hour-long meditation on something so constant, so ambient, that most people never realize it’s shaping their lives—let alone the rooms they build.

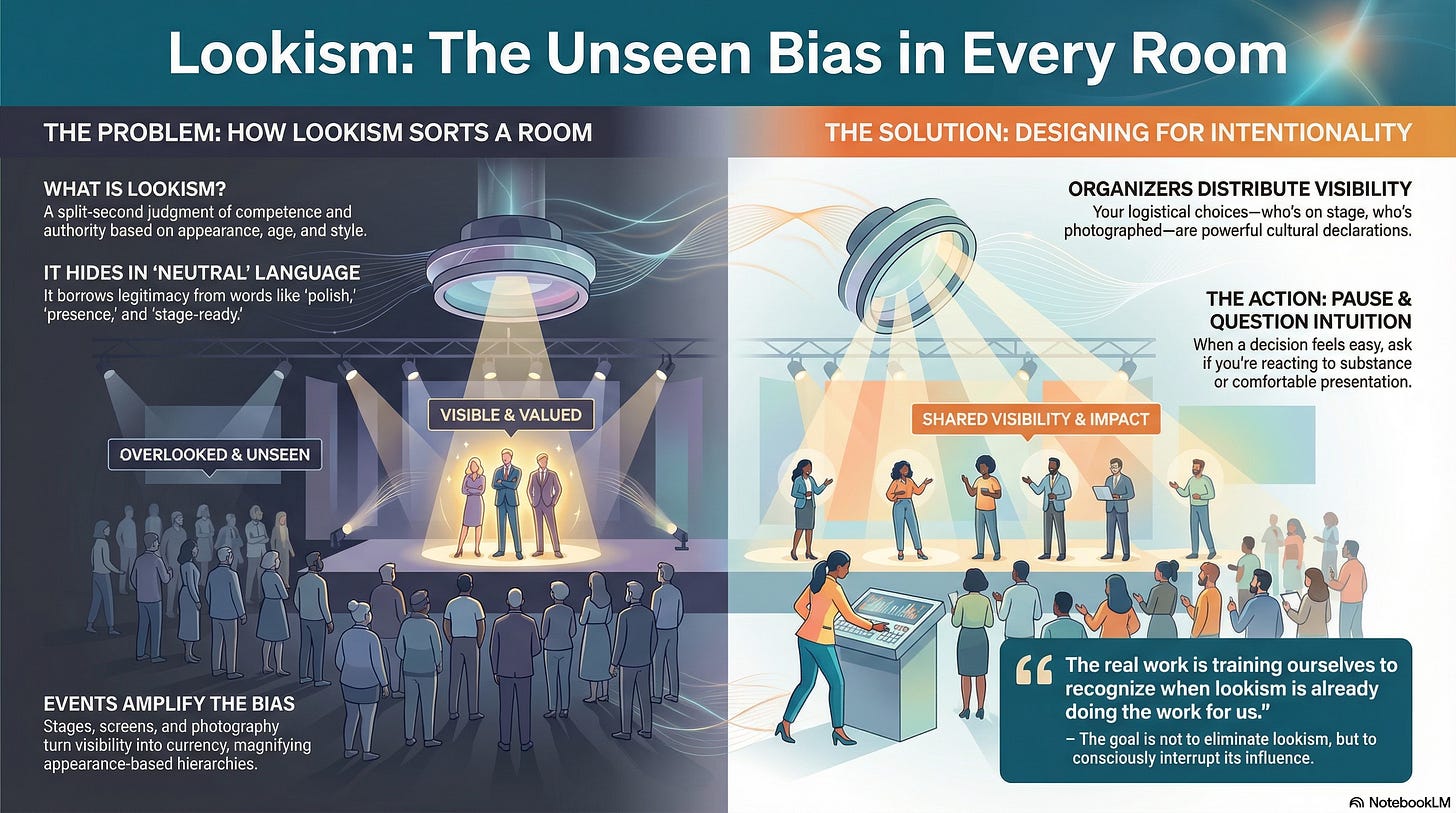

Lookism is not a belief so much as a habit of perception. It is the split-second judgment made before intention has time to intervene—the quiet sorting of faces, bodies, ages, and presentations into assumptions about competence, authority, warmth, or relevance. It hides inside words we consider neutral, even virtuous: polish, professionalism, presence, “stage-ready.” Because it borrows legitimacy from taste rather than ideology, it rarely triggers self-examination. And because nearly everyone participates in it, it remains one of the few biases we can still practice without admitting we are doing so.

As Christopher spoke, what struck me was not how radical the idea sounded, but how familiar it felt. Lookism is simply the adult, better-dressed version of what we all learned in high school. The moment people walk into a room—a welcome reception, an opening cocktail, a conference lobby softened by lighting and name badges—the social physics engage immediately. Clusters form. Gravitational centers emerge. Certain people are approached first, listened to longer, laughed with more easily, often without anyone quite knowing why. Others are quietly positioned at the edges. We like to believe professionalism civilizes these instincts, but adulthood mostly gives us better language, not better reflexes. We call it networking now, but the choreography is the same.

This is why lookism matters so deeply in the gathering economy. Events are environments built on visibility. They are rooms designed for watching, remembering, and evaluating. Stages elevate bodies into symbols. Screens magnify faces into authority. Photographers curate the visual memory of who mattered. If lookism is a low hum in everyday life, gatherings amplify it into surround sound.

It would be dishonest, however, to suggest the events industry has stood still. In truth, it has evolved faster than many sectors, sometimes faster than the corporations it serves. Over the past decade, stages that once defaulted to narrow archetypes have been reshaped by deliberate choices. Gender balance is now expected. Racial representation is no longer exceptional. Accessibility has moved from compliance to design principle. Organizers have become quiet cultural editors, reshaping the visual grammar of leadership simply by insisting that rooms reflect the world as it actually exists.

The broader culture reinforced this shift in unmistakable ways after the murder of George Floyd. Marketing departments recalibrated almost overnight. An all-white commercial no longer felt merely outdated; it felt inaccurate. Representation stopped being a political signal and became a truth test. Once audiences saw themselves in the frame, there was no appetite for going back. The genie did not return to the bottle, and no serious industry should expect it to.

Which is why the current grumbling about “too much wokeness” misses the point. This is not ideology; it is accuracy. Once justice bends in a direction that finally resembles reality, it rarely snaps back into its old shape. Events understand this instinctively. A stage that looks wrong now feels wrong. A panel that defaults to the familiar triggers questions rather than comfort. Consciousness, once raised, becomes baseline.

And yet lookism persists, precisely because it hides inside our ideas of polish and presence. We have diversified who speaks, but we have not fully diversified what authority looks like. We still associate symmetry with intelligence, thinness with discipline, youth with relevance, conventional beauty with trustworthiness. We still praise “stage presence” without interrogating which bodies we have been trained to see as presentable. Because lookism does not announce itself as prejudice, it survives every audit.

This is where the events industry carries an outsized responsibility. Organizers are not merely producers; they are wholesalers of influence. They distribute visibility at scale. A marketer shapes perception through images; an organizer shapes it through bodies—through proximity, elevation, and memory. Conference stages mint legitimacy. Photo galleries become the historical record of who mattered. Decisions that feel logistical are, in fact, cultural declarations.

Christopher understood this instinctively. Perhaps because he came from an unexpected political place, his clarity landed harder. He believed deeply in personal agency, yet saw plainly that perception itself is not neutral. He understood that lookism was not ideological; it was human. And once named, it demanded responsibility.

There are moments when society does choose to confront appearance bias—when it becomes too visible to ignore. Laws protecting natural hairstyles are one example. But most lookism remains legally unprotected and culturally untouched, which makes gatherings—places where we still meet one another in full sensory reality—one of the few arenas where it can be addressed through intention rather than regulation.

Christopher Mario died on September 8, before he could see how far that porch conversation would travel. This piece is dedicated to him: his clarity, his generosity of thought, his refusal to let easy categories do the thinking for him. And to the hope that the rooms we build next might finally loosen their grip on inherited hierarchies and begin to reflect the full spectrum of who we are, not just the polished fraction we’ve been trained to reward.

The work ahead isn’t about eliminating lookism. That would be a fantasy, and fantasies don’t design good rooms. The real work is training ourselves to recognize when lookism is already doing the work for us—when instinct, familiarity, or comfort has quietly taken the pen from our hands. The moment an organizer slows down long enough to notice how a room is sorting itself, authorship returns. What follows is not moral correction but professional rigor: the discipline of seeing clearly, of choosing deliberately, of refusing to let inherited hierarchies masquerade as inevitability. In an industry that already trains obsessively for safety, accessibility, and logistics, learning to see how appearance shapes belonging is simply the next layer of craft in the gathering economy.

In an industry that trains obsessively for safety and logistics, accessibility still breaks when bodies don’t match what the room was trained to expect. Learning to see how appearance shapes belonging is simply the next layer of craft in the gathering economy.

Brilliant work connecting lookism to the gathering economy specifically. The insight about organizers being "wholesalers of influence" who distribute visibility at scale really clarifies why this matters beyond just individual bias. I've noticed at conferences how spatial dynamics alone can entrench hierarchies before anyone speaks, kinda like the room itself has prferences. If we're serious about redesignnig these spaces, maybe the next layer is training event teams to audit not just who's on stage but how the entire physical setup either amplifies or undermines those choices.