Before the Dream, There Was the Room

A Martin Luther King Jr. Day reflection on leadership, convening, and the craft of organizing people before history notices

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the country reliably returns to the same images: the sweep of the National Mall, the marble gravity of the Lincoln Memorial, the voice rising into history. We quote the lines we know by heart. We honor the dream. What we rarely do is look closely at the work that made those moments possible—the quieter, less cinematic labor of gathering people together and holding them there long enough for something real to happen.

This story, and the reenactment video that accompanies it, is my way of honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. by taking that work seriously. Not by re-quoting him, but by studying how he actually moved people. Not as a monument, but as a convener. Not only as a moral figure, but as someone who understood—early, instinctively, and relentlessly—that change happens in rooms before it ever happens in public.

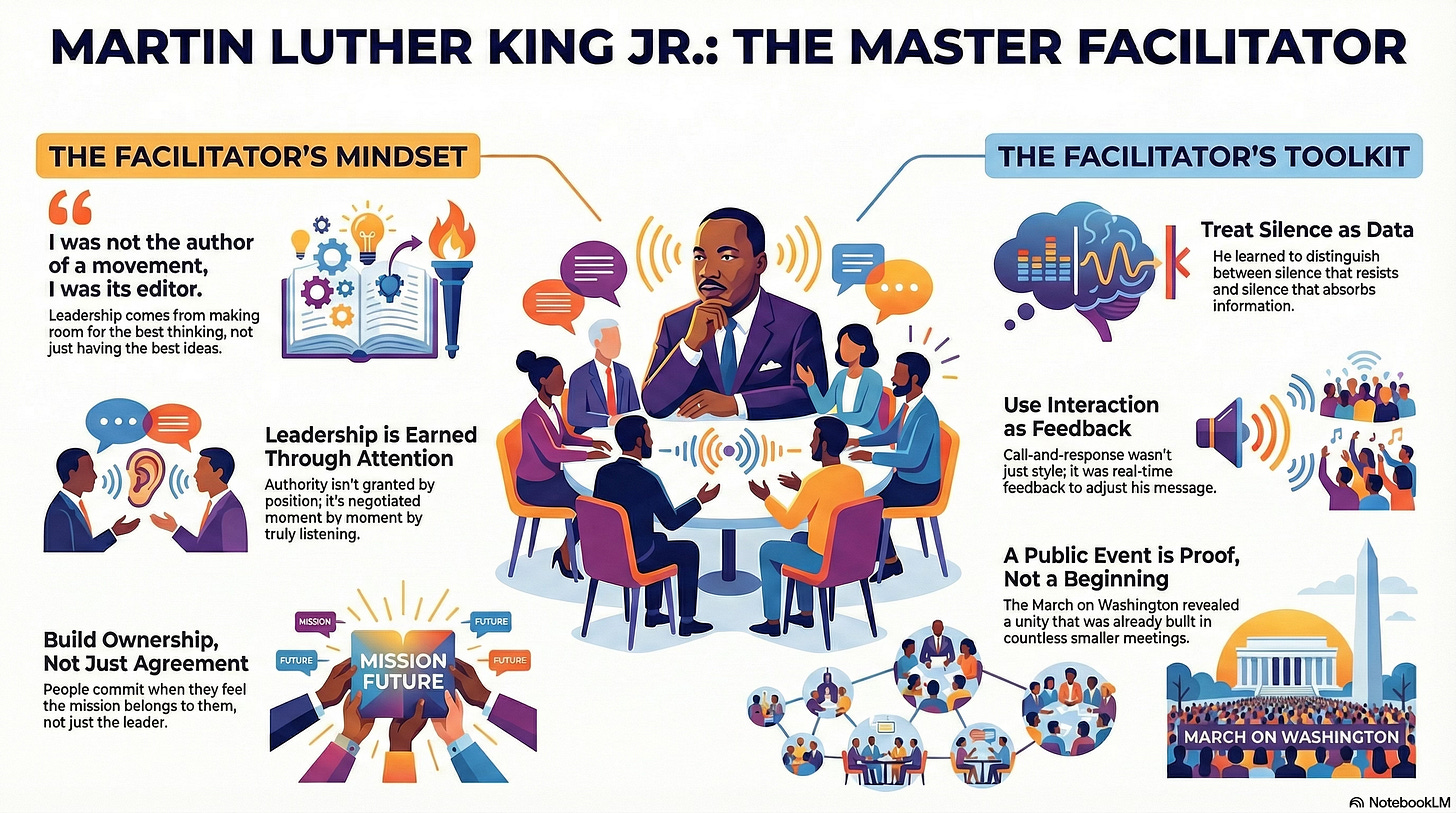

Long before King learned how to command a national stage, he learned how to hold a room. Not a metaphorical one, but a literal one: rooms with folding chairs, side conversations, skepticism, fear, impatience, and consequence. He grew up inside those rooms. His father’s church, Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta (ebenezeratl.org), was not a sanctuary of polite listening. It was a place where people talked back, where affirmation arrived audibly, where resistance surfaced without apology. Even as a boy, King was absorbing a lesson most leaders never consciously learn: authority is not bestowed by position. It is negotiated, moment by moment, through attention.

By the time he reached Booker T. Washington High School (Atlanta Public Schools history), King was already navigating the delicate choreography of public life—who spoke, who deferred, who was heard, who wasn’t. He was bright, visibly marked by expectation, and already aware that intelligence alone could alienate as easily as it could persuade. When he entered Morehouse College at fifteen (morehouse.edu/about/history), that awareness sharpened. Morehouse did not teach him how to speak; it placed him in rooms where disagreement was neither abstract nor academic, where ideas were tested against responsibility. Leadership, he learned, was less about certainty than about accountability to people who did not always agree with you, and who would not follow you simply because you spoke well.

The church refined what school revealed. Sermons were not performances; they were negotiations. A preacher spoke, the room answered, and meaning emerged somewhere between the two. King learned to hear signals most people mistake for noise: a murmur that meant recognition, a silence that meant resistance, a stillness that meant something had landed and needed time. Call-and-response was not ornament or tradition for its own sake. It was feedback—immediate, unfiltered, impossible to fake. He learned pacing the hard way. Rush a room past its fear and you lose it. Linger too long in anger and it fractures. Repetition was not redundancy; it was rehearsal. When people repeated a phrase, they were not applauding it. They were testing whether they could live inside it.

When leadership arrived early—and it did—it came cautiously. In Montgomery, at twenty-six, newly arrived and largely unentangled in local rivalries, King was elevated through the Montgomery Improvement Association (Stanford King Institute overview) not because he dominated rooms, but because he could keep them intact. People sensed that he would not rush them past doubt, nor pretend bravery was effortless. In moments when jobs, safety, and dignity were all on the line, that restraint mattered. Movements do not move because someone is eloquent. They move because someone can turn scattered human intention into coordinated behavior, over time, under pressure, with consequences. That work happens in rooms.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott (King Institute archive) is often remembered as an eruption, a sudden moral awakening that swept a city. In reality, it was a sustained act of organization that required meetings, discipline, communication, and collective agreement renewed day after day. People had to show up repeatedly, regulate their anger, absorb inconvenience, and trust one another. None of that happens automatically. It has to be facilitated. King understood that the boycott was not just a protest; it was a prolonged exercise in participation, one that trained people how to be together under stress.

Years later, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (National Museum of African American History & Culture) would come to symbolize the movement’s moral force. Recent attention to Bayard Rustin—including the film Rustin (Netflix)—has rightly restored the machinery behind that day: the permits, the coalitions, the choreography required to move hundreds of thousands of people through a city without collapse. Rustin deserves his place in the story as the master organizer who made scale possible (King Institute on Rustin). But the machinery worked because the muscle memory already existed. By the time people gathered on the National Mall, they had practiced being together. They had practiced discipline, restraint, listening, and collective decision-making. The march did not create unity. It revealed it. King understood this distinction instinctively. The event was never the beginning. It was the proof.

Watching King through this lens—as a facilitator rather than a monument—changes how his leadership reads. The reenactment video that accompanies this story takes a deliberate risk. It imagines what King’s method might sound like if he were speaking not to a march, but to today’s leaders, organizers, and event professionals—people whose work still depends on rooms, participation, and collective choice. The point is not to recreate a historical speech. It is to translate a method. King’s power did not reside only in his words. It resided in his understanding of how people come to move together.

That is why this piece runs on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Honoring King does not mean freezing him in amber or repeating his most familiar lines. It means learning from him. Especially those of us whose work depends on bringing people together—in movements, in companies, in institutions, and in the rooms where decisions are made. King did not treat gatherings as accessories to leadership. He treated them as its infrastructure. Churches, mass meetings, boycotts, and marches were not symbolic backdrops. They were carefully held environments where fear could be acknowledged without taking over, where disagreement could surface without breaking the group, and where courage could be rehearsed before it was demanded in public.

We tend to talk about Martin Luther King Jr. as if he emerged fully formed—a voice, a vision, a destiny. The truth is more instructive. He was a young man who learned early how rooms work. He listened before he led. He earned trust one gathering at a time. That is why he matters now, not only as a moral figure, but as a model for anyone who leads people. Because whether you are running a movement, a company, or an organization, the work is the same: creating conditions where people can think together without splintering, commit without coercion, and act without being pushed.

King did not just dream in public. He practiced in private. He learned in rooms that did not yet belong to him. That is not mythology. It is craft. And on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, it is a craft worth remembering—especially for those of us who believe that events, gatherings, and facilitation are not peripheral to change, but central to how history actually moves.

Further Reading / Verification

The King Center – Biography & chronology: https://thekingcenter.org/about-tkc/martin-luther-king-jr/

Stanford Martin Luther King Jr. Research & Education Institute: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu

Montgomery Bus Boycott archive: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/montgomery-bus-boycott

March on Washington (NMAAHC): https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom

Bayard Rustin background: https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/rustin-bayard

Great article! There’s a lot to learn from this reflection.